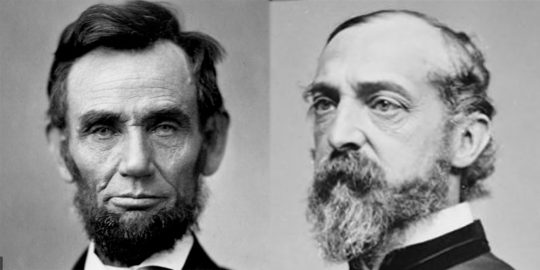

I have learned so many great lessons from Abraham Lincoln, which is why I’ve been studying him since I was a little boy. His letter to Major General Meade (cover photo, right) following the Battle of Gettysburg illustrates my point entirely. It also leads me to some hard questions. Have you ever done, or said something and then felt disappointed and/or foolish for having said or done it? I know I have. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve behaved in such a way, only to wake up the next day regretting what I said or did. It’s even easier for us to stick our feet in our mouths these days with all the kneejerk opportunities on social media.

When Confederate General Robert E. Lee retreated from the Gettysburg battlefield in July of 1863, torrential rains began to fall. The Potomac River, which he and his Army of Northern Virginia were north of, flooded over. With no way of re-suppling his troops and trapped on the wrong side of the river, he had no viable escape route. By most accounts, Meade, with more men than Lee to begin with, and fully capable of re-provisioning his troops through wide open supply lines, chose not to pursue his opponent. In the meantime, Meade’s ambivalence gave Lee just enough time to regroup, build bridges and escape across the river. Lincoln was so distressed that he wrote a letter to Meade, admonishing him for the lost opportunity. However, before Lincoln sent the letter, he reevaluated the situation, filed the letter away and never sent it. Fortunately, the letter, despite not reaching its intended target, was preserved.

A portion of the letter reads below…

Executive Mansion,

Washington, July 14, 1863

Major General Meade

You fought and beat the enemy at Gettysburg; and, of course, to say the least, his loss was as great as yours– He retreated; and you did not; as it seemed to me, pressingly pursue him; but a flood in the river detained him, till, by slow degrees, you were again upon him. You had at least twenty thousand veteran troops directly with you, and as many more raw ones within supporting distance, all in addition to those who fought with you at Gettysburg; while it was not possible that he had received a single recruit; and yet you stood and let the flood run down, bridges be built, and the enemy move away at his leisure, without attacking him.

Again, my dear general, I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape– He was within your easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in connection with the our other late successes, have ended the war– As it is, the war will be prolonged indefinitely. If you could not safely attack Lee last Monday, how can you possibly do so South of the river, when you can take with you very few more then (than) two thirds of the force you then had in hand? It would be unreasonable to expect, and I do not expect you can now effect (affect) much. Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasurably because of it.

I beg you will not consider this a prosecution, or persecution of yourself– As you had learned that I was dissatisfied, I have thought it best to kindly tell you why.

[Endorsed on Envelope by Lincoln:]

To Gen. Meade, never sent, or signed.

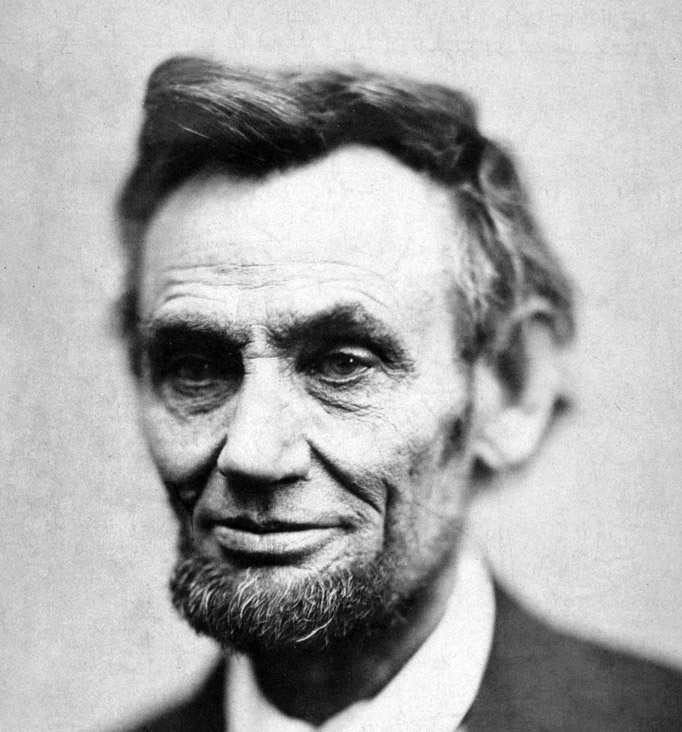

One can easily understand Lincoln’s angst. The war had been raging for more than two years. Hundreds of thousands of men had already died. And of course Lincoln clearly understood that as long as Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia remained a fighting force, the war would continue, and of course it did for another two years, nearly. Think of the men who could have been saved. Lincoln was right. Meade could have destroyed Lee’s army; the opportunity was clearly lost. Yet, after sleeping on it, Lincoln began to view things in a different light. How could he admonish a man for sacrificing so much during the Battle of Gettysburg just because he did not do more? No doubt, Meade and his men, like their enemies, were exhausted and licking their wounds. Certainly Lincoln, through his own reflective thought, was licking his own.

No doubt, writing the letter served as great therapy for the troubled President. After careful consideration, not sending it was even better therapy. Somewhere in this, there’s a great lesson for all…a lesson in leadership. Lincoln knew better than to move and/or make decisions based on kneejerk reactions. He thought long, hard and deliberately on the subjects he faced during his presidency, even in the crucible of the moment. Even though he was right, and knew it, he chose not to send the letter. So the next time you’re ready to fire off that kneejerk reaction on your favorite social media platform, take a breath; rest on it…ponder it. It’s likely that once you simmer down, collect and organize your thoughts, the response you ultimately craft will be more appropriate and far more effective. And even sometimes, as in the case of Lincoln with Meade, the best response is no response. Something to think about…

Don Radebaugh

Find the History Mystery Man on Facebook and YouTube.