By Don Radebaugh — Good Friday turned out to be not all that good for Abraham Lincoln, unless being on the other side is better than living as we know it.

Leading up to that fateful day, the stress and strain of four years of Civil War — the price paid by more than 600,000 men who died — were distinctly visible on Lincoln’s face on Good Friday, April 14, 1865. Despite the pain and suffering that came with his first term — including the loss of his second son Willie — on this day he was the happiest he had been in years.

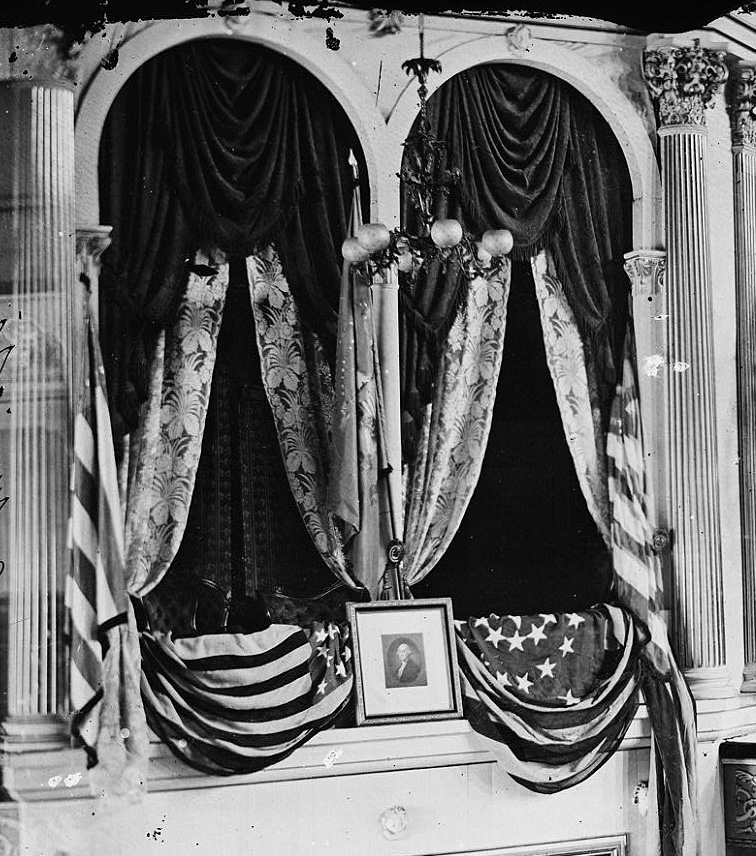

And for good reason. The war was all but over because Robert E. Lee had finally surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant just five days earlier. And, under his own generous Reconstruction plan, Lincoln could look forward to four more years in the Executive Mansion (White House) without a Civil War breathing down his neck. On the home front, his oldest son Robert Todd was home from college, and he and Mary could look forward to the play “Our American Cousin” later that evening at Ford’s Theatre.

“His whole appearance, poise and bearing had marvelously changed,” said Lincoln’s new Secretary of Treasury Hugh McCulloch. “He was, in fact, transfigured. That indescribable sadness which had previously seemed to be an adamantine element in his very being, had been suddenly exchanged for an equally indescribable expression of serene joy as if conscious that the great purpose of his life had been achieved.”

In fact several of Lincoln’s closet family and associates — those who were with him on his last day — commented on his abundance of cheerfulness, so much so it had startled them.

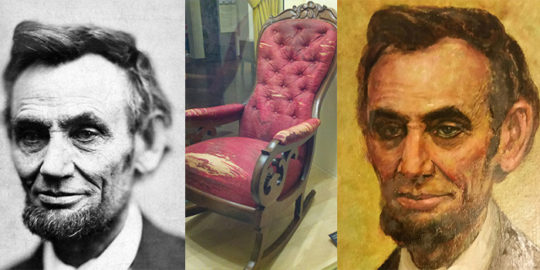

But we all know how it goes from here. Lincoln, already late to the play, finally took his seat in the infamous chair. Then John Wilkes Booth entered the balcony box where he and Mary were sitting, aimed a single-shot Philadelphia Deringer pistol at the back of Lincoln’s head and pulled the trigger. Lincoln died the next morning at 7:22 a.m. in a boarding house across the street.

The chair Lincoln was assassinated in was immediately confiscated by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton as a piece of evidence during the investigation before it went into 30-some years of storage at the Smithsonian. Eventually, it was purchased and moved to The Henry Ford museum in Dearborn, Michigan where it now sits behind glass for all to see.

However, in between Ford’s Theatre and The Henry Ford, the chair lived in a damp corner of a warehouse at the Smithsonian for at least 30 years. Anyone and everyone hanging around could opt for a seat on the red rocker, if not for the mind-blowing enormity of the act, then for bragging rights.

“It appears that people had access to it,” said Jim Johnson, senior manager of creative programs at The Henry Ford. “It was put into storage in what turned out to be a hidden break area, we think, for workers, because that’s when the chair gets messed up.”

For years, the chair was damaged by water leaks, plaster dust, wet plaster and hair grease. Men often wetted and greased their hair down in that era, which explains the big stain on the back of the chair. Of course, for those who visit the chair, the stains are often mistaken as dried blood from Lincoln when in fact, they’re not. There was very little blood from Lincoln at the scene. Dr. Leale, already in the house for the show, came calling soon after the fatal shot. Lincoln was then laid out on his back across the box floor. Feeling around the back of Lincoln’s head, Dr. Leale discovered the hole and unplugged the clot, which in turn relieved pressure from Lincoln’s brain. It also caused Lincoln’s heart and breathing to come back to a more normal rhythm, enough to buy another eight hours anyway. No matter how it would turn out, the bullet that entered the back of his head behind the left ear and lodged just behind the right eye, had torn clean through the brain of Abraham Lincoln.

With Lincoln headed on his own journey among the stars, the now infamous red rocker was already on a tour of its own. The journey started with Ford Theatre manager Harry Clay Ford — no relation to Henry Ford — who would often bring the chair to Ford’s Theatre for his special guests.

After the assassination and the subsequent investigation, Uncle Sam sent the chair to the Smithsonian where it sat in a warehouse in storage. Unfortunately, everyone and anyone — access was not an issue then as it is today — sat in the chair adding further wear and tear to the silk and staining the back of the chair with their commonly greasy hair.

After some 30 years at the Smithsonian, Blanche Chapman Ford, the widow of Harry Clay Ford, petitioned the government to get the chair back, according to Johnson. Soon after it was returned to her, the chair went up for auction.

Israel Sack, a prominent antique dealer, then bought the chair for Henry Ford in 1929 at a price of $2,400, reported a Washington Post story in 2010, about a month after Ford had opened Greenfield Village. The chair has been in the Henry Ford collection ever since.

In the mid 1990s, a major conservation effort was taken on the chair…the fragile silk fabric was encased in a polyester sheer fabric to keep the original silk in place.

And now it “belongs to the ages” at The Henry Ford. Thanks for procuring the artifact Mr. Ford. Your museum and adjoining Greenfield Village are off-the-charts amazing. What an American treasure for the Motor City metropolis and beyond.

Editor’s Note: Lincoln’s suffering could not be more apparent on the face of the 16th President after four years of bloody Civil War. It’s comforting to know that he died happy, something he had not been for so long.

@DonRadebaugh

Source: http://www.mlive.com/lansing-news/index.ssf/2015/04/how_lincolns_assassination_cha.html