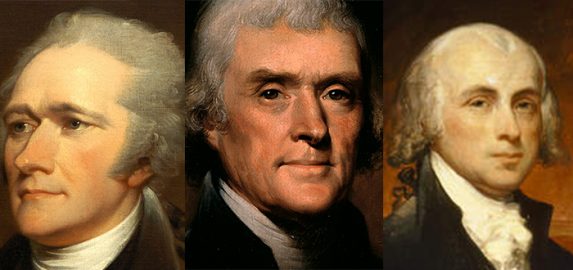

By Don Radebaugh — If you were paying attention in history class, you’ve probably heard about the Missouri Compromise or the Compromise of 1850; but how about the Compromise of 1790? Heard of that one? Unless you’ve seen the Broadway musical Hamilton, or you’re a student of the post-American Revolutionary period, you may not know about the earlier compromise, or in this case, a “dinner table bargain” between political friends/rivals James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, as brokered by Thomas Jefferson in June of 1790.

Without the compromise/political bargain, America, on the heels of the Constitutional Convention and Ratification (1787-1789), may have crumbled right then and there, just as it was trying to get off the ground and go.

To cut to the chase, the political bargain brokered by Jefferson was essentially this: Madison agreed to let Hamilton’s fiscal program pass while Hamilton agreed to use his influence to assure that the permanent location for the new nation’s capital would be on the Potomac River in Virginia. Two of the three players in the deal were from Virginia, it’s worth noting.

And in fact on July 9, 1790, the Residence Bill, by a vote of 32 to 29, was passed, which placed the country’s capital on the Potomac River after a 10-year tenure in Philadelphia. Then, by a similar vote (34 to 28) on July 26, the House passed the Assumption Bill (Hamilton’s fiscal program).

Two years later, Jefferson, Secretary of State under President George Washington, told Washington that the deal he brokered that night was the greatest political mistake of his life.

“It was unjust,” said Jefferson. “And was acquiesced in merely from a fear of disunion, while our government was still in its infant state.”

As was often the case, Hamilton out-maneuvered his opponents, which is why he so often angered his political rivals. Not just that Jefferson and Madison hated to lose; but that, as events would unfold, Hamilton was usually proven right in regards to the debates at hand. In this case, Hamilton understood, at least fiscally speaking, what the nation needed to survive through the short-run gamut in order to thrive for the long-term greater good. Looking back on the American experience, its success is now a foregone conclusion; but in the very beginning, it was anything but.

Keep in mind, Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury under Washington, and Madison had just collaborated as co-authors of the Federalist Papers, leading the charge for an expanded national government, complete with sovereign power over the states…all this while Jefferson served as America’s Minister in Paris from 1784 – 1789. And when Hamilton began writing his Report on the Public Credit, Madison was one of the first people he consulted with.

But something happened inside Madison’s head during the six months that preceded the dinner table bargain, shifting from a Federalist platform, under a collaboration with Hamilton, to Jefferson’s side among the Anti-Federalists. Madison had already been collaborating with Jefferson over a series of letters before Jefferson returned to America in March of 1790.

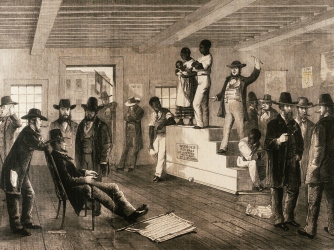

It’s also worth noting that the political debates on Assumption and the Residency question (where to put the nation’s capital) were not the only issues lighting up the contestants on the congressional floor in 1790. They were also simultaneously dealing with the explosive issue of slavery. Petitions were already coming forward — the first from a Quaker delegation out of Pennsylvania — that questioned the African slave trade, which was supposedly protected inside the Constitution until 1808. No matter what side you were on regarding slavery, no one had an answer for it that would satisfy all. Slavery was already so woven into the economic fabric of the south, that if immediately abolished, the entire economy of the new country could crumble at the onset. Right or wrong, the 1808 clause put the slavery issue in pause mode for 20 years while America weaved through the political entanglements of its time.

It’s also worth noting that the political debates on Assumption and the Residency question (where to put the nation’s capital) were not the only issues lighting up the contestants on the congressional floor in 1790. They were also simultaneously dealing with the explosive issue of slavery. Petitions were already coming forward — the first from a Quaker delegation out of Pennsylvania — that questioned the African slave trade, which was supposedly protected inside the Constitution until 1808. No matter what side you were on regarding slavery, no one had an answer for it that would satisfy all. Slavery was already so woven into the economic fabric of the south, that if immediately abolished, the entire economy of the new country could crumble at the onset. Right or wrong, the 1808 clause put the slavery issue in pause mode for 20 years while America weaved through the political entanglements of its time.

“We have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go,” Jefferson said. “Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.”

At any rate, as spelled out in the Report on the Public Credit, Hamilton’s calculations had the total debt of the United States at a mind-blowing $77.1 million, $11.7 million of which America owed to foreign governments. The rest was labeled as domestic debt ($40.4 million) and state debt ($25 million), both largely a result of the Revolutionary War. All understood that America needed a plan to restore public credit, not only to put the new nation on solid/stable financial ground, but so that foreign governments would not consider America the financial laughing stock of the free-market world. It was, however, Hamilton’s specifically-worded proposal to restore public credit that freaked out Madison the most.

On the domestic debt side, Hamilton proposed that all citizens who owned government securities should be reimbursed at full value, despite the fact that veterans of the American Revolution who had received securities as payment for their service in the war had already sold them to speculators at a fraction of their original value. Madison sliced it up three ways.

“One of three things must be done,” said Madison. “Either pay both, reject wholly one or the other, or make a composition between them on some principle of equity.”

To Hamilton, Madison’s proposal would have been an administrative catastrophe for the new government to sort out at this most precarious time when the country needed to move forward unobstructed.

But that was just the tip of the iceberg. Most of Madison’s angst came from Hamilton’s idea of “assumption,” placing financial authority with the central government, and largely taking it away from the states. To Hamilton, it’s exactly what the new country needed to keep it together in the crucible of the moment. To Madison, it was exactly what the fledgling country fought against in the American Revolution, while it was being controlled, dominated in fact by England’s strong and well-entrenched central government.

While there were several states in deep debt and in need of financial repair, some, like Virginia, had paid off most of its wartime debts. That said, Madison wanted to ascertain the specific amount each state would have “assumed” before each state would be obligated to pay federal taxes. By Madison’s calculations, Virginia would transfer about $3 million of debt to the federal government, all the while owing $5 million in federal taxes. It was that good old-fashioned fear of a bigger monster consuming a smaller one, kind of like England trying to control the American colonies all over again.

Despite the complications of it all, to Hamilton, it was all very simple. The new country was in a giant fiscal mess and he was determined to, not only restore public credit across the globe, but place America on firm financial footing so it could stay alive, grow and prosper. On the subject of domestic debt, Hamilton regarded Madison’s plan of distinguishing between original and current security holders as ludicrous, just for the administrative nightmare it would cause alone. Besides, who was Madison to lecture a Revolutionary War veteran like Hamilton…Madison who had not fought in America’s war for independence.

On the Assumption side, Madison himself had advocated the assumption of state debts on several occasions in the 1780s. In fact it was Madison, during the Constitutional Convention, who was an ardent advocate of federal sovereignty over the states.

It probably didn’t help that neither Jefferson or Madison understood the financial structure necessary to carry a fledgling new country forward the way that Hamilton did. It was also widely understood that many of Virginia’s privileged class were heavily in debt to British and Scottish creditors, including Jefferson who carried his debt to his grave. In short, Hamilton understood fiscal health and what it would take to get there. Jefferson and Madison, although arguably brilliant in their own right, did not. And until America’s foreign debts were paid and her credit restored overseas, the United States would not be taken seriously in European capitals.

And so, with each side thinking they got the best of the other, the dinner table bargain (Compromise of 1790) was struck between Hamilton and Madison. We’ll give you your “assumption” Hamilton, if you’ll give us (both Jefferson and Madison were Virginians) the nation’s capital. To Hamilton, taking the capital from Philadelphia to its site along the Potomac (present day Washington D.C.) was small potatoes in order to get his grand financial plan in place.

In the 1790s, securing the nation’s capital in your home state of Virginia seemed like a tasty nugget for Jefferson and Madison that would provide untold benefits down the road. And, there were several other cities in the new American country that felt the same way. The leading candidates negotiating for the capital were Annapolis, Baltimore, Carlisle, Frederick, Germantown, New York, Philadelphia, the Susquehanna and Trenton.

It’s also worth noting that the negotiations that facilitated the Compromise of 1790 more than likely didn’t go down in one dinner table bargain as Jefferson suggested…that it was in fact a lengthier process that led to the “final supper” in June of 1790. What did most probably happen at the last dinner was the negotiation of Virginia’s part in the Assumption Bill. And wouldn’t you know it…the final version of the Assumption Bill would reduce Virginia’s total obligations so that the state’s debt assumed by the federal government would be the exact amount it would owe in federal taxes — $3.5 million. Imagine that.

In the end, Madison and Jefferson got what they thought they wanted — settlement of the nation’s capital along the Potomac before Hamilton got what he knew he wanted — Assumption. On solid, federal financial footing, the country marched forward under the new two-party political system. And if the new two-party platform wasn’t perfect, at least it provided the necessary framework for the arguments of the day to be heard while the nation continued to gel.

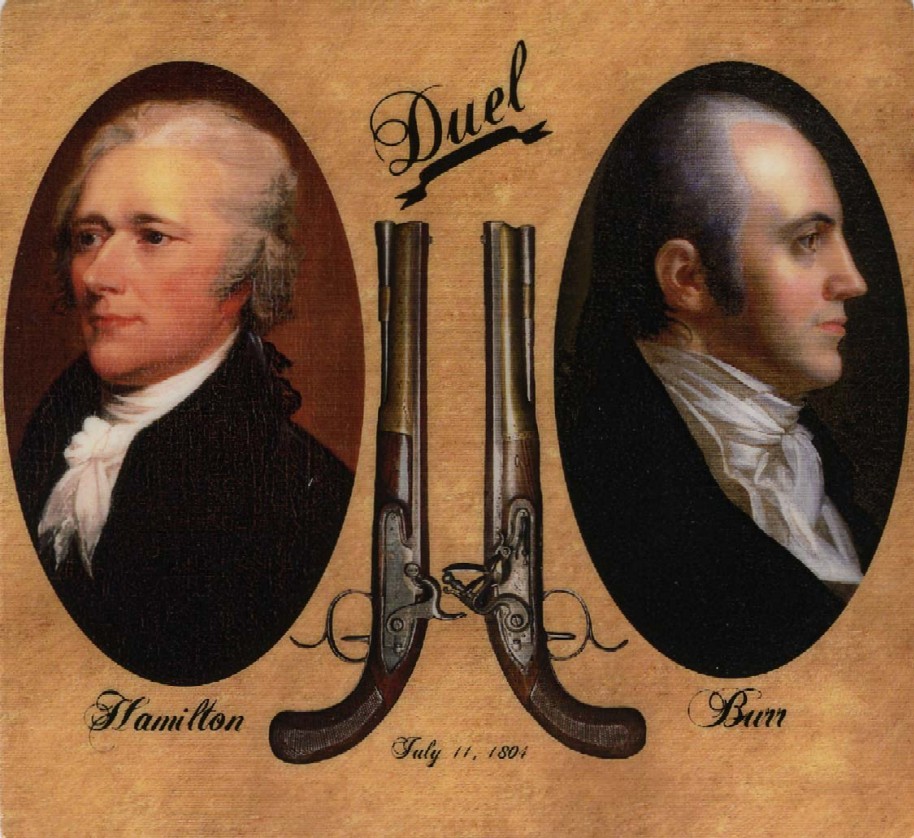

Feeling a bit duped after the deal was done, Jefferson pressed on with his own political agenda, elected third President of the United States, defeating John Adams for the honor. Madison followed Jefferson as President. Hamilton, on the other hand, never got the chance for the nation’s highest office, shot dead in a duel by Jefferson’s Vice President Aaron Burr in 1804, thus ending a 15-year feud between Hamilton and Burr.

Back in September of 1787, three years before the dinner table bargain, the ever brilliant Hamilton made an interesting prediction.

The newly created federal government would either “triumph altogether over the state governments and reduce them to an entire subordination…or in the course of a few years, the contests about the boundaries of power between the particular governments and the general government will produce a dissolution of the government of the Union.”

Sounds like Hamilton knew what he was doing after all.

Source: Founding Brothers, by Joseph J. Ellis, copyright 2000.

@DonRadebaugh on Twitter, or History Mystery Man on Facebook.