Part 4

By Don Radebaugh — If Crosley Radio Corporation stock wasn’t immune to the stock market – it went from almost $100 a share in late October to $19 in less than a month – Powel and Lewis Crosley were far better prepared for the country’s hard times ahead. While much of America bought on credit – the bills all at once coming due – the Crosley Corporation wisely operated on a cash basis. They didn’t owe anyone. And when the new Seagate mansion in Sarasota, Florida was complete – at a cost of nearly a million – the Crosley family moved in just after the holidays. Then Powel purchased his new 75-ft. yacht, Argo.

Powel and Gwendolyn returned to Cincinnati in March of 1930 for the grand opening of the WLW 8th-floor studios in the Arlington Street building. And no longer was WLW just a means of advertising for Crosley products. In 1930, despite the Depression, the station turned a profit of $43,464. The Crosley Radio Corporation also added a new product in ’30 – the Roamio car radio. In ’31, the Crosley refrigerators continued to ship for $99.95. As so often was the case, Crosley got his refrigerators to the markets first, and cheaper than anyone else.

Despite the ongoing Depression, 1932 was another banner year: Powel IV was born and the FRC granted Crosley an experimental license to broadcast at 500,000 watts. In the dark times of the 1930s, families gathered around their radios for a source of light. While the Golden Age of Radio was not only welcome relief from tough times, new Crosley radio models like the Arbiter and the Buddy also served as handsome furniture units that made living room center pieces.

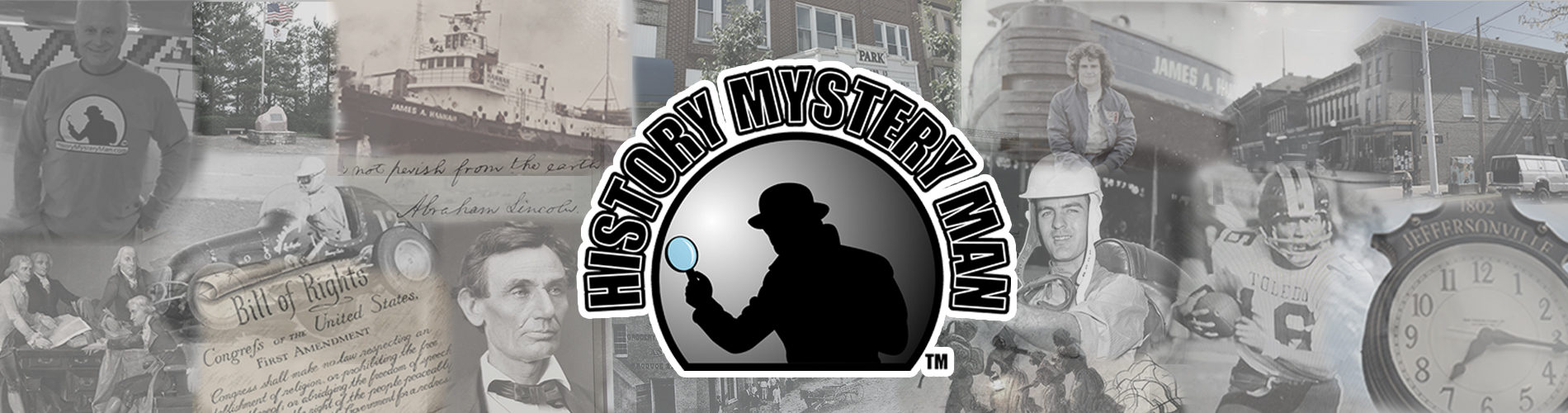

In February of 1933, Crosley’s new Shelvador refrigerator hit the stores for $99.50, revolutionary in that the door was equipped with shelves. Powel saw the potential, purchased the patent, and sent it down the line for mass production. Production soared as the market for home appliances boomed. The Moto-Iron, washing machines and the Temperator space heater were also in production.

In March, construction began on the 500,000-watt transmitter, 136 tons of steel erected 831 feet into the air. The “Nation’s Station” would become more than entertainment; it shaped public opinion going forward. More hit shows debuted on WLW with Dr. Konrad’s Unsolved Mysteries, a quiz show called Dr. I.Q. and Ma Perkins, a fictional series aimed at housewives. Ma Perkins was sponsored by Proctor & Gamble’s Oxydol soap, and the show became known as a “soap opera” giving rise to the reference that endures today.

If things were going well for the Crosley Corporation, such was not the case for the home team. The Cincinnati Reds, major league baseball’s first professional team, was enduring one losing season after another. Worse yet, if things didn’t turn around, the Reds would be leaving town. Cincinnati, the birthplace of professional baseball, was endangered of losing its team, without a wealthy backer that is. Apparently, that wasn’t an option for Powel Crosley, who then purchased 3,200 of the 6,000 outstanding shares — $240,000 worth – to take control of the Cincinnati Reds. Redland Field became Crosley Field overnight. There would now be little doubt as to who was in control of the team when a giant model of the Shelvador refrigerator was placed above the scoreboard for all to see. All the hoopla did nothing for the batting average, however. In 1934, the Reds finished last for the fourth consecutive year.

Then, history was made when on May 2, 1934, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt turned on WLW’s 500,000-watt new transmitter from the White House by pressing a golden telegraph key. Congratulatory telegrams poured in from Albert Einstein, CBS President William S. Paley, Guglielmo Marconi and more. To celebrate, Powel bought a new plane, a Northrup Delta for $40,000. And, despite a workers’ strike in early 1935 at the Arlington Street factory, Crosley ramped up production in spite of the strike.

Then, history was made when on May 2, 1934, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt turned on WLW’s 500,000-watt new transmitter from the White House by pressing a golden telegraph key. Congratulatory telegrams poured in from Albert Einstein, CBS President William S. Paley, Guglielmo Marconi and more. To celebrate, Powel bought a new plane, a Northrup Delta for $40,000. And, despite a workers’ strike in early 1935 at the Arlington Street factory, Crosley ramped up production in spite of the strike.

Fortunately, he had his right-hand-man, his brother Lewis to nip the strike in the bud; but not without a few concessions. Workers would now be paid weekly, rather than three times a month, and there would be overtime after 40 hours work.

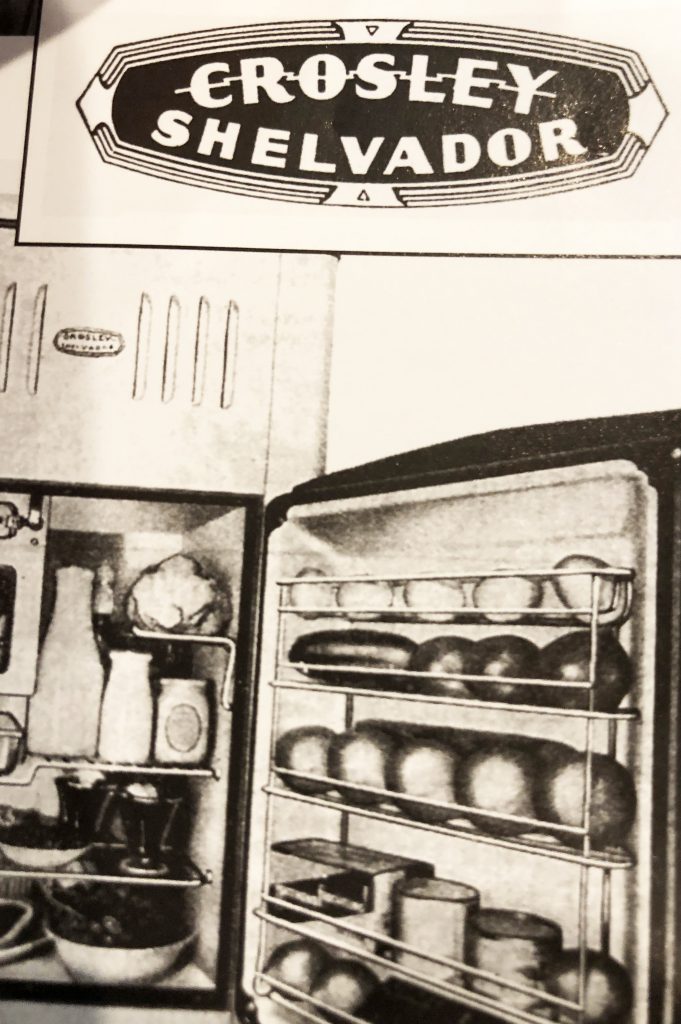

Meanwhile, lights were going up at Crosley Field for what would be the first night game in major league history. Delayed till May 24, 1935 because of rain the day before, President Roosevelt lit the first bulb from the White House, and best of all, the Reds won 2-1 before 20,000 fans. After winning their third game in a row, attendance was up at Crosley Field. The novelty of baseball under the lights no doubt helped. In fact, in 1935, the Reds’ attendance more than doubled and their record improved. The team even ended up in the black for the first time in 10 years, earning $165,000.

Despite the strike of ’35, company profits were over a half-million. Shelvadors were now accounting for 50% of Crosley Radio Corporation sales. On average, 2,000 Shelvadors rolled off assembly lines per day, and refrigerator sales were up 63% overall. It looked pretty good from Powel Crosley’s eyes too. He was now the No. 1 man in radio. He had the most powerful broadcast station in the world and he owned the Cincinnati Reds. He bought more planes, two more yachts, and noodled out his next dream of building a Crosley car for the masses.

Part 5

With the ongoing Great Depression all around, Powel Crosley almost seemed to ignore it. In 1936, WLW, the Nation’s Station, had 150 employees on staff. And despite the devastating January floods that caused one of his subsidiary factory buildings to burn, resulting in a half-million in damage, plans went ahead to build yet another factory in Richmond, Indiana, a one-mile brick building that would host two production lines, one for the Shelvador and the other for Crosley cars. Construction began on the Richmond factory in ’37, the same year Powel invented the ice cube tray featuring the removable aluminum grid inside. It seems there was no end to his ingenuity and vision. And, Doris Day, who would one day become a Hollywood film star, debuted on WLW.

In 1938, Powel got another baseball brainstorm, and moved homeplate 20 feet toward the fences. The Reds responded with more home runs. It was also in ’38 when television began to take hold, and NBC and CBS started conducting broadcast tests. To keep pace, Powel inquired to RCA, Westinghouse and GE regarding the cost of building a television transmitter. They told him it’d take at least 18 months to build one. That did not sit well with Powel Crosley. “Powel wouldn’t wait 18 months for anyone,” Lewis said. He was right. Powel turned to his own engineers and told them to design something in 30 days. His engineers told him it’d be at least 90 days. They got it done in 60. As was always the case, Powel envisioned it; Lewis rolled up his sleeves and made it happen.

The Crosley Radio Corporation officially became the Crosley Corporation in 1939. While things looked rosie from Powel Crosley’s eyes, the world chess board was getting more dangerous by the moment. In Europe, Adolph Hitler’s army stood at the border of Czechoslovakia. Back on the home front, anticipation mounted for the Crosley car while Martians attacked the earth when the War of the Worlds, narrated by Orson Welles and John Houseman, was heard across the country on CBS radio. The broadcast was fictitious of course but many listeners thought it was real…again, reminding all of the power of radio back in the day. Crosley, not immune to regulation, got some bad news in ‘39 when the FCC ordered the station to reduce its transmission from 500,000 watts back to 50,000. Powel of course appealed the decision; but the FCC again denied the renewal of WLW’s superpower license. It was also in ’39 when Powel’s beloved wife Gwendolyn died after a long battle with Tuberculosis. She was buried at Spring Grove Cemetery on February 28. On March 1, WLW’s big transmitter went off the air. Powel, devastated over his wife’s death, holed up in his Pinecroft mansion for a month while Hitler marched into the Czech Republic. In April, the first Crosley cars, built in the mile-long Richmond factory, began rolling off the line. On April 28, Powel gathered up the press and debuted the cars at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, one was a coupe for $325 and the other a sedan for $350. As always, he was first to the market with the least expensive product for the masses. “I have always wanted to build a practical car that would not only operate at a low cost but sell at a low cost,” Powel said. “And I believe I have it here.”

It was also in ’39 that Hitler attacked Poland while the Reds, still riding the momentum created when Powel bought the team, made their World Series appearance, their first since 1919. They played against the New York Yankees. They lost.

In 1940, new Crosley models, the deluxe sedan, station wagon and pickup truck made a splash at the New York Auto Show. And despite being reduced to 50,000 watts, the experimental license still allowed WLW to continue broadcasting at 500,000 watts after midnight. The overnight broadcasts could be heard around the world, providing welcome relief from home for American soldiers overseas. Powel’s WLW short wave field of long distance broadcasts also served as a propaganda machine for all of Europe. Hitler could hear it too. “Cincinnati liars,” he called them.

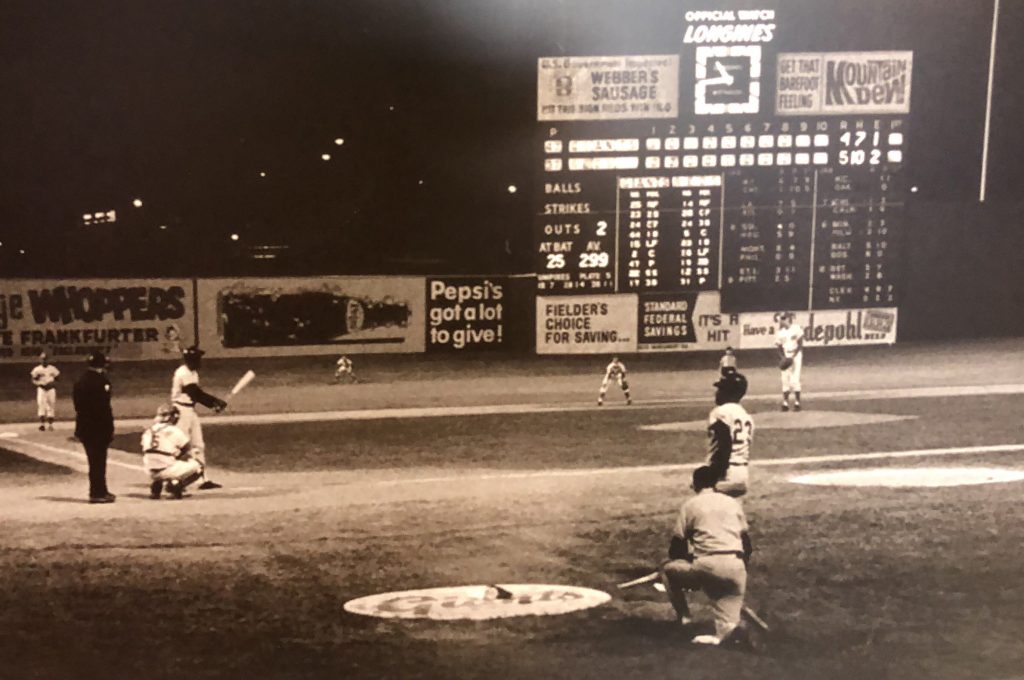

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, WLW went on the air with immediate news bulletins. Shortly thereafter, the U.S. government created its first official radio station: The Voice of America. But the Voice of America needed its own dedicated broadcast facility, so they turned to WLWO, Crosley’s shortwave transmitter. It was also at that time when Powel and Lewis Crosley, with a keen sense of patriotic duty, converted their factories over to war production. They also, for the first time, borrowed money – to the tune of $9 million dollars – to equip and modernize their factories for the war effort. Keep in mind, their capital was still greater than their debt, which is how they always operated. Crosley planes were also pressed into service and Powel’s yachts were drydocked, except for the Sea Owl and Wego, both of which went to the United States Coast Guard. Crosley Corporation also went to work on the top-secret “proximity fuze,” as instructed by the United States government. The fuze was the precursor to the “smart bomb.” Prior to the fuze, anti-aircraft strategy consisted of determining flight trajectory and speed and then flooding a pre-determined zone of fire with shell fragments in hopes of bringing down the aircraft. Now, there would be a bomb that could search out its target and explode when in “proximity” of the aircraft, and it was done with a radio transmitter and receiver. In layman’s terms, the Crosley Corporation produced a tiny radio station in the nosecones of artillery shells. The transmitter would send out radio waves that would bounce off the plane and send the signal back to the receiver. When the artillery shell was in proximity of the aircraft, a fuse attached to the bomb would be ignited. It was first tried in December of 1942 from the light cruiser Helena when Japanese pilots approached. It worked. “In that instant,” wrote historian Ralph Baldwin, “the history of warfare changed.” The smart bomb, triggered by the ‘proximity fuze’, and mass-produced by the Crosley Corporation of Cincinnati, was a success.

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, WLW went on the air with immediate news bulletins. Shortly thereafter, the U.S. government created its first official radio station: The Voice of America. But the Voice of America needed its own dedicated broadcast facility, so they turned to WLWO, Crosley’s shortwave transmitter. It was also at that time when Powel and Lewis Crosley, with a keen sense of patriotic duty, converted their factories over to war production. They also, for the first time, borrowed money – to the tune of $9 million dollars – to equip and modernize their factories for the war effort. Keep in mind, their capital was still greater than their debt, which is how they always operated. Crosley planes were also pressed into service and Powel’s yachts were drydocked, except for the Sea Owl and Wego, both of which went to the United States Coast Guard. Crosley Corporation also went to work on the top-secret “proximity fuze,” as instructed by the United States government. The fuze was the precursor to the “smart bomb.” Prior to the fuze, anti-aircraft strategy consisted of determining flight trajectory and speed and then flooding a pre-determined zone of fire with shell fragments in hopes of bringing down the aircraft. Now, there would be a bomb that could search out its target and explode when in “proximity” of the aircraft, and it was done with a radio transmitter and receiver. In layman’s terms, the Crosley Corporation produced a tiny radio station in the nosecones of artillery shells. The transmitter would send out radio waves that would bounce off the plane and send the signal back to the receiver. When the artillery shell was in proximity of the aircraft, a fuse attached to the bomb would be ignited. It was first tried in December of 1942 from the light cruiser Helena when Japanese pilots approached. It worked. “In that instant,” wrote historian Ralph Baldwin, “the history of warfare changed.” The smart bomb, triggered by the ‘proximity fuze’, and mass-produced by the Crosley Corporation of Cincinnati, was a success.

Through ’41 and ’42, Crosley Corporation, Cincinnati’s biggest employer with more than 10,000 men and women, mass-produced the fuze and more. The Cincinnati and Richmond factories were busting out war materials seven days a week – gun sights, gun turrets, military radios, fuzes, portable generators, radar equipment, stoves for cooking in the field and more.

One thing that was not competing well on the home-front was Crosley’s Pup and Bull Pup automobiles, manufactured to compete with Toledo, Ohio-built Jeeps. None were ordered in quantity. Powel went back to the drawing board and came out with Snow Tractors and the Crosley Tug. None of it satisfied the U.S. government, whose choice during the war remained with Jeep. By January of 1945, the tide of the war turned as allied forces advanced on Germany. The war was nearly over. “The fuze won the Battle of the Bulge,” said General George S. Patton. Powel stepped up plans to resume car manufacturing after the war. He told reporters, “The post-war Crosley car will be bigger and produce more power but will not be placed in competition with the ‘big car’ market.”

Source & photo credits: Crosley, by Rusty McClure, Copyright 2006