By Don Radebaugh — By now the gears in Powel Crosley’s head had churned and turned to the point where a concrete plan began to take shape. If Crosley intended on mass-producing his own radios, then it only made sense that he needed his own radio station to help market his new product. On July 21, 1921, the Department of Commerce granted Crosley his first broadcast license – call letters 8XAA. He went on air three evenings a week. With no designed order of content, they made it up as they went along. In the beginning, there was a lot of record playing and civic-minded lectures. Or, if you could play a musical instrument, and you were nearby, you might be summoned for duty. At any rate, the first orders for Crosley’s new Harko radios came in on Sept. 21. In March of 1922, his Harko Sr., already marketed on his new radio station, hit the stores.

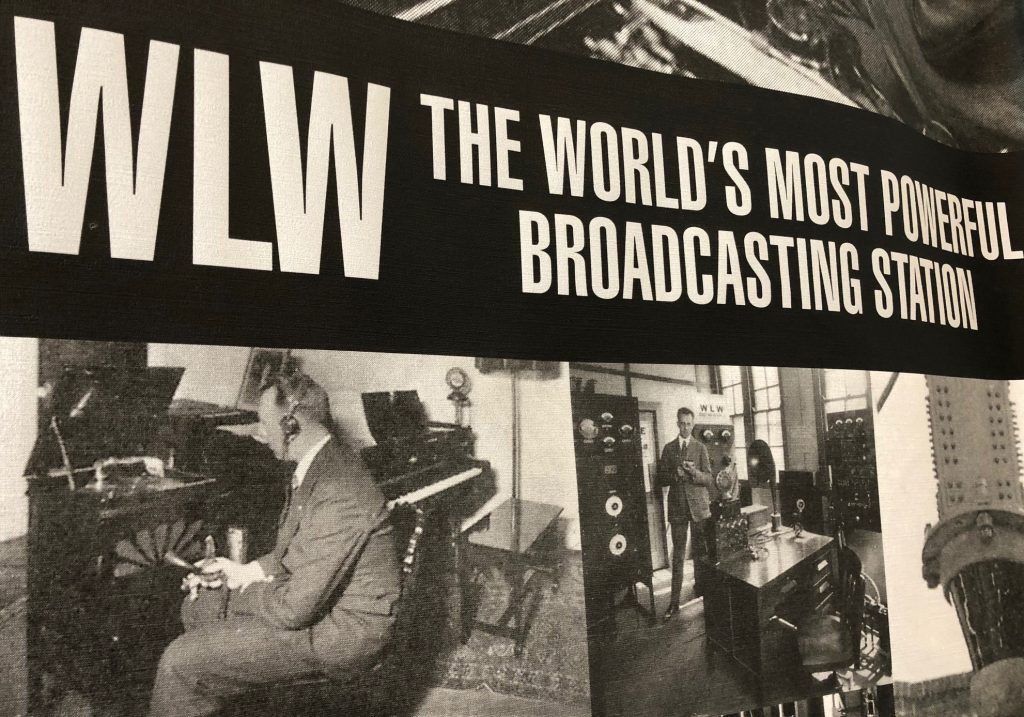

Then on March 2, 1922, the new world of wireless radio would never be the same when Crosley was authorized commercial license #62 to broadcast at 360 meters and given the call sign WLW. On March 23, WLW, at 710 on the AM dial, went live on the air.

“WLW, Cincinnati’s great radio broadcasting station, erected and located at the Crosley Manufacturing Company, inaugurates a regular broadcasting program schedule of news, lectures, information and music, and all forms of audible entertainment.”

“WLW, Cincinnati’s great radio broadcasting station, erected and located at the Crosley Manufacturing Company, inaugurates a regular broadcasting program schedule of news, lectures, information and music, and all forms of audible entertainment.”

Despite Crosley’s formal announcement, they still made up the station’s programming as they went along. Crosley himself was the Master of Ceremonies. His special guest was Cincinnati Mayor George P. Carrel. With a radio studio smack-dab in the middle of his factory, Crosley enhanced his Harko radio with the Model V, Model X and Model XV.

Like any start-up operation, there were initial problems at WLW. With other new radio stations coming out, broadcasting at 360 meters got crowded really fast. The result was increased radio interference. Undaunted, Crosley packed a bag and headed to Washington D.C., and he wasn’t stopping at the front gate. He was there to speak with Warren G. Harding, President of the United States. When the meeting was over, Crosley marched off with an increased broadcast wavelength of 400 meters and a Class B Station rating with a minimum transmitter power of 500 watts. The increase in watts would be sign of bigger things to come. Crosley didn’t do things small; he only thought big, and 1922 was a perfect example. In that year alone, he went from a mid-sized manufacturer of automobile accessories to one of the largest radio manufacturers in the world. His Harko radios were flying off the shelves.

To be sure, there is much more to Crosley’s success than one man with a vision.  Someone had to turn his visions into reality, and that ‘someone’ was his younger brother Lewis Crosley. If Powel could dream it, Lewis could build it. Whether it was overseeing the construction of their new factory, outfitting an assembly line to accommodate Powel’s next vision or managing the sticky business of striking workers, Lewis managed the nuts and bolts of the day to day operations. As Orville Wright was to his brother Wilbur, Lewis was to Powel. The Crosleys were not only brothers; they were a team.

Someone had to turn his visions into reality, and that ‘someone’ was his younger brother Lewis Crosley. If Powel could dream it, Lewis could build it. Whether it was overseeing the construction of their new factory, outfitting an assembly line to accommodate Powel’s next vision or managing the sticky business of striking workers, Lewis managed the nuts and bolts of the day to day operations. As Orville Wright was to his brother Wilbur, Lewis was to Powel. The Crosleys were not only brothers; they were a team.

The next item on Powell’s to-do list carried a $40,000 price tag. He bought Precision Audio, and with it, the more important Armstrong license, which came with the long sought-after regenerative circuit. This allowed WLW to usurp broadcast time as necessary, without having to share the frequency. And in the summer of 1923, Lewis performed a broadcast test from Redland Field where the Cincinnati Reds played. After a few innings, and satisfied it was working, he pulled the plug. Back at the corporate offices, the phones were ringing off the hook, most wanting to know why he didn’t broadcast the entire game. The corporate office at that time was a 100,000 sq. ft. stone building at Coleraine and Sasafras Streets. And by late 1923, Crosley was one of the top names in the radio business.

Part 3

In 1924, Powel Crosley was on top of the world. It seemed like a good time to fold Precision Equipment completely into the Crosley corporate umbrella, giving birth to the Crosley Radio Corporation. And on April 15, 1924, WLW was granted permission to broadcast the opening day of Cincinnati Reds baseball, spurring a broadcast movement in major league baseball that shared “America’s Pastime” with the masses.

While WLW continued to rev up, Powel kept opening up his wallet, running ads in “Radio Broadcast”, “Radio Digest”, “QST” and the Saturday Evening Post. The full-page ad in the Post cost $7,000, a tidy sum in its day. Powel wanted to let his distributers and retailers know that he and his parent corporation were willing to spend that kind of money, fully committed to bringing customers in stores, to hammering home the Crosley brand name and message – “Better – costs less.”

Meanwhile, back at the Colerain St. factory, the second and third floors were humming with radio production while new state-of-the-art WLW studios were being built overhead. The studios were outfitted with a new Baldwin concert piano and xylophone, and could accommodate a complete orchestra or choral group.

In 1925, WLW was broadcasting on a wavelength of 423 meters. Like the year before, the station broadcasted the Reds home-opener. The “Roaring 20s”, from Powel’s perspective, were living up to the name. By 1926, WLW was broadcasting 40-plus hours a week. There was good news on the home-front too. Powel and his wife Gwendolyn and their 16-year-old boy Powel III were ready to move into their new mansion, Pinecroft. At a cost of $750,000, the home was outfitted with chauffeurs, gardeners, gatekeepers, maids, cooks and housekeepers. To top it off, Powel purchased a new 40-ft. yacht, Muroma. And through the rest of the 20s, the money poured in and the family prospered.

Always ready with his next vision, Powel, the idea man, brainstormed his way through the world of refrigeration, coming up with a unit he called the Icyball. Lewis, as always, handled the production side. Lewis found a way to make it happen, working the magic to turn his brother’s vision into reality. It worked. More than 20,000 Icyballs were sold in the first year of production. In the meantime, WLW was up to 5,000 watts. In June of 1927, the Federal Radio Commission (FRC) – the precursor to the Federal Communications Commission – moved WLW from 710 to 700 on the AM band. Chain broadcasting networks, which would become the wave of the future, began popping up with NBC and CBS becoming incorporated. And Charles Lindbergh completed his 27-hour flight across the Atlantic in the Spirit of St. Louis, becoming the first human to fly solo across the Atlantic.  The amazing feat no doubt helped fuel Powel’s fascination with airplanes, which is probably why he bought two Waco 10 aircrafts, then rebranded them with Crosley logos on each side and renamed them the Crosley Stork.

The amazing feat no doubt helped fuel Powel’s fascination with airplanes, which is probably why he bought two Waco 10 aircrafts, then rebranded them with Crosley logos on each side and renamed them the Crosley Stork.

In the late 1920s, the boon years continued for the Crosley Radio Corporation. The FRC granted WLW the rights to broadcast at 50,000 watts while a new steel building in Mason, Ohio was being erected to house the new 50,000-watt transmitter. Crosley stock rose to 57 dollars a share while WLW was broadcasting over a hundred hours a week. On Monday, October 29, 1928, Powel gave a speech for the formal dedication of the new transmitter while President Franklin D. Roosevelt threw a gold switch from the Whitehouse to officially put the 50,000-watt transmitter over the air. Through 1928, $18 million dollars of radios were sold while Powel began design of Crosley’s first airplane. Powel also bought two square blocks adjacent to the Colerain factory, fronting Arlington Street. New drawings were done up for a new eight-story building, adding 200,000 sq. ft. of production space. Fourteen active assembly lines, each over a hundred feet long, were already in operation.

In 1929, Crosley stock was selling at $95 a share while initial prototypes for Powel’s Moonbeam C-1, C-2 and C-3 airplanes were complete. Then he bought a 193-acre tract of land in Sharonville, Ohio and built his own Crosley Airport. The new tower at the Arlington Street factory took the building to 10 stories, all this while a new home in Sarasota, Florida was already halfway to completion. Crosley Radio Corporation stock continued to climb, and the Icyball was selling faster than workers could churn them out while more Moonbeams were being built. Back at the new Arlington factory, Lewis continued to hire new employees while they worked at full capacity on the first four floors, all this while concrete was being poured for the seventh and eighth floors, which would house company offices and yet another new WLW studio. The company payroll was now at 5,000, Cincinnati’s largest employer.

Then, the stock market crashed. Black Tuesday, Oct. 29 turned the country in a direction no one was prepared for. The Great Depression, the single most catastrophic economic downturn in western civilization, had begun.

Source & photo credits: Crosley, by Rusty McClure, Copyright 2006