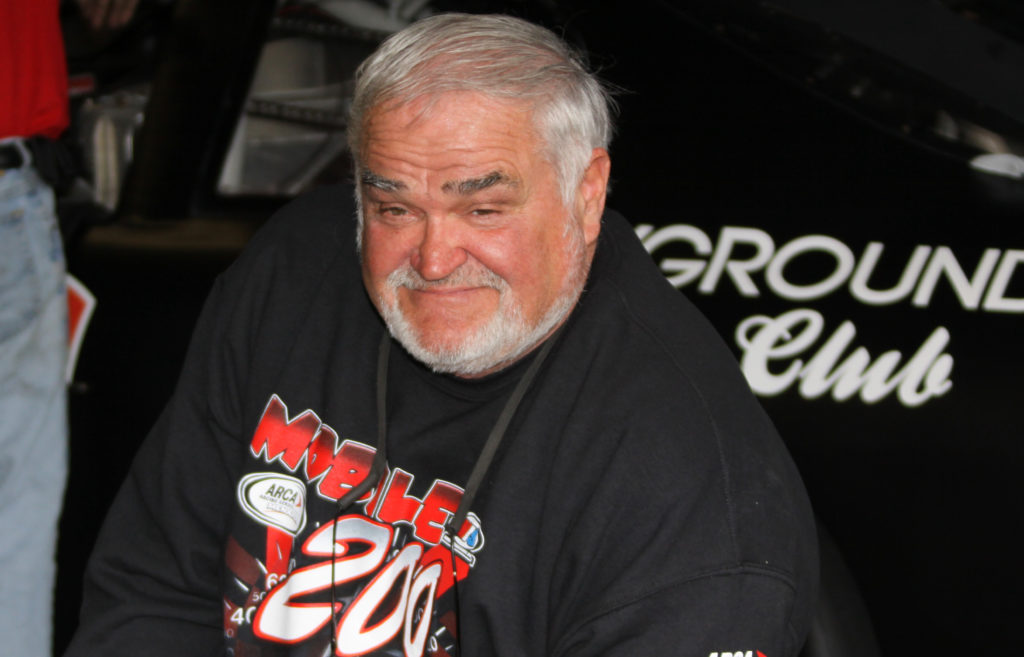

By Don Radebaugh – In recognition of a job well done, some high school graduates celebrate with high-fives and then travel to far away fun spots for senior class trips. Others…don’t. You can put Chattanooga, Tennessee’s Wayne Hixson in the latter category. It was 1967, and Hixson, still a teenager, was drafted into the Vietnam War. Welcome to tropical Southeast Asia. Please enjoy your stay.

If there is a metaphoric door from boyhood to manhood, Hixson, a “grunt” in the Marine Corps, marched through it overnight. One day, he was planning his future with close friends and family in small town America. The next day, he was among strangers on a military transporter plane to some place he had never heard of. As the song goes, and as Hixson would come to find out, “Uncle Sam got himself in a terrible jam…way down yonder in Vietnam.”

If there is a metaphoric door from boyhood to manhood, Hixson, a “grunt” in the Marine Corps, marched through it overnight. One day, he was planning his future with close friends and family in small town America. The next day, he was among strangers on a military transporter plane to some place he had never heard of. As the song goes, and as Hixson would come to find out, “Uncle Sam got himself in a terrible jam…way down yonder in Vietnam.”

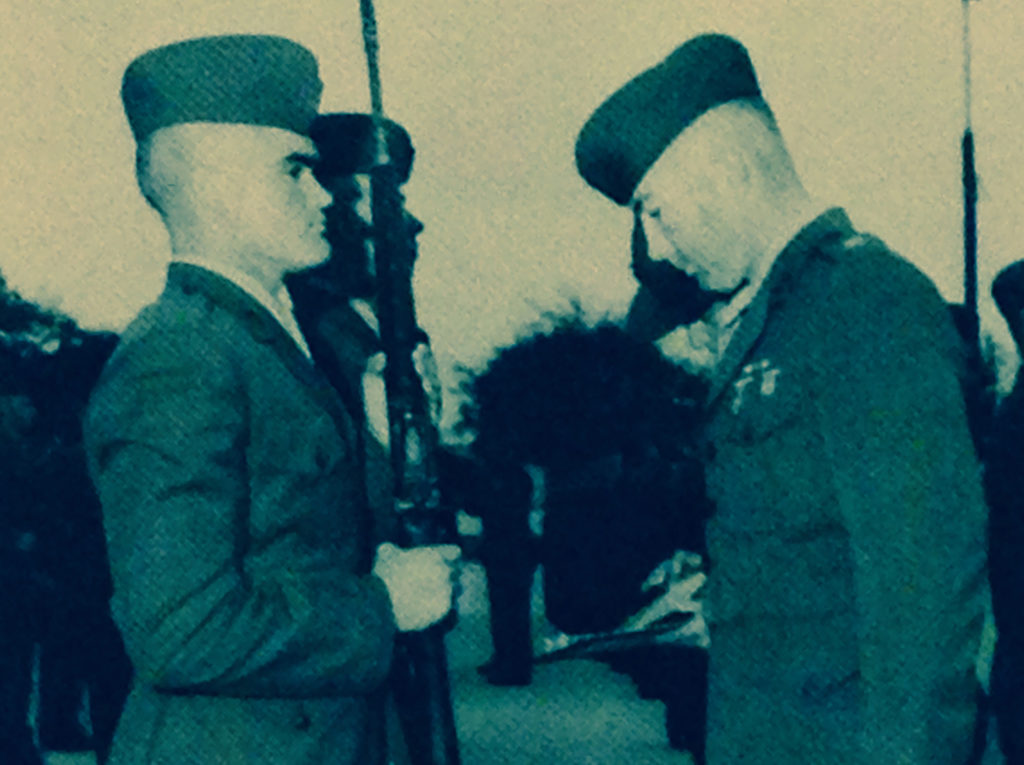

After two years of service during which he received three Purple Heart Medals, he should have returned to the States a hero, much like any soldier would be, and should be, treated upon their return. But, Vietnam was an extremely unpopular war, and the soldiers paid the ultimate price…in the jungles of Vietnam and in airports across America on the way back.

“You have to remember, there were so many people against that war,” said Hixson. “The soldiers were drafted; it’s not like everyone signed up. Parents didn’t want their kids killed. And there were so many protests against us.

“We never lost a battle but we lost the war. When it wasn’t beneficial to the election people, they got out of it.”

As hard as it is to fathom today, Hixson, at that time, was advised by his military commanders to remove his uniform for his return to the United States.

“When you traveled back to the States, you might start out in uniform, but when you got close to the States, you were advised to change clothes. They said, that way you wouldn’t have as much trouble. But, you still had your service haircut, so they would still have a pretty good idea of where you’d been. Back then, most everyone had long hair.

“The government didn’t want to do anything about it. You had the Dems on one side and the Republicans on the other, and all they wanted to do was argue about it. There were so many kids killed. I was one of the lucky ones.”

As a “lucky” one, Hixson was wounded three times in battle. He received a Purple Heart for each hit.

“Yep, I have three of them (Purple Hearts). You get hit three times in battle, and you’d get three Purple Hearts; that’s how it works.

“Yep, I have three of them (Purple Hearts). You get hit three times in battle, and you’d get three Purple Hearts; that’s how it works.

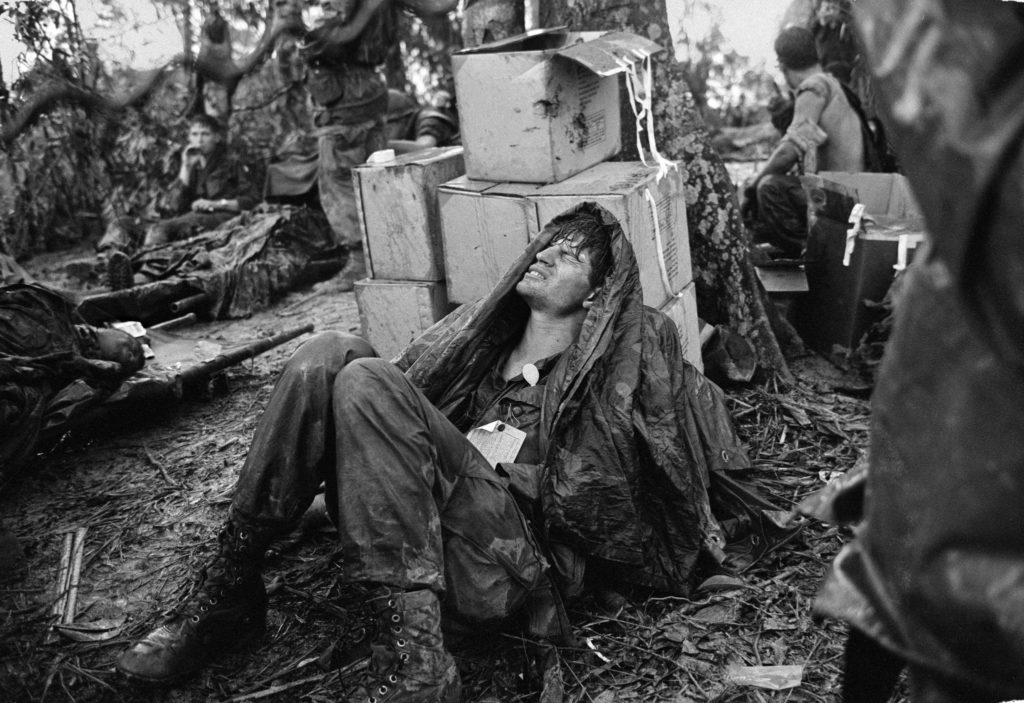

“It was pretty bad up where we were at. We were up on a DMZ and it was during the Tet Offensive, patrolling from the mountains to the ocean for about six months.”

By definition, a DMZ is classified as an area in which treaties or agreements between nations, military powers or contending groups forbid military installations, activities or personnel. A DMZ often lies along an established frontier or boundary between two or more military powers or alliances.

In other words, a DMZ is a dangerous, unchartered no-man’s land. Hixson found himself in five fire-fights in the DMZ.

“You’d get hit with shrapnel from artillery, or grenades. First time I got hit in the arm. It was serious but not bad enough to get shipped back, so they fixed you in the field. Then I got hit in the side and back of the head on the last one, and that one got me good, so they shipped me to a hospital in Guam. When I got out of the hospital the last time, they turned me into a Brig Sergeant. I traveled all over the world…Japan, Germany, France, Australia, the Philippines…just about anywhere there was a prisoner that went UA (Urgent Action) that I had to go pick up.”

If he wasn’t hit, he often tended to the wounded.

“When someone got hit, you’d gather ‘em up, care for them the best you could, and carry ‘em out to a helicopter. Then you’d wait around for another one.”

Facing temperatures sometimes of up to 120 degrees in the wet jungle terrain, soldiers regularly became afflicted with serious infections such as ringworm, malaria and others. Hixson and his men were often in the field for as long as a month.

“We’d stay out anywhere for 20-30 days before you’d go back to your base, which was basically a bunch of tents. Then we’d be at the base for about a week, then go out again. If it wasn’t hot, it was raining.

“We ate what they called sea rations. They’d drop the rations in out of a helicopter about every four or five days or so. We’d squeeze five or six meals out of each box that we carried around with us.”

Hixson spent six months of his service in the jungles of Vietnam, and was considered a ‘grunt’, which was slang for a ‘boots-on-the-ground’ Marine in Vietnam.

“I was a 311; that was the number of it. A 311 grunt.”

Per law, men had to register for the draft when they turned 18. When the choices were Vietnam, jail or draft-dodging by going to Canada, some young men panicked and devised ways to fail the military’s physical exam, including mutilating themselves or starving themselves.

“I suppose there were all sorts of ways to try and get out of it. I just did what they said, and went.”

By the end of 1965, more than 45,000 young men were called. When the monthly draft call rose from 17,000 to 35,000 per month, young people across the nation began engaging in civil disobedience. On November 27, 1965, the March on Washington for Peace in Vietnam took place, attracting tens of thousands of protesters.

Files, in the custody of the National Archives and Records Administration, contain records of 58,220 U.S. military fatal casualties of the Vietnam War.

In civilian clothes, Hixson returned to America in 1969. The Vietnam War raged on for another six years, ending officially April 30, 1975.

“I’ve been out of the military for more than 40 years. They’ve really changed things on how they do things today compared to how they did it back then.

“It’s hard to explain what you went through unless you went through it. I learned a lot from it. I hear some people complain about everything when we all ought to be thankful for all we got. It could be a lot different.”

Today, he’s still got shrapnel living in his aging body and suffers the consequences of the Agent Orange that continually rained down on him in the jungles and rice paddies of Vietnam…cancer, numerous operations…they’re still carving on Wayne Hixson.

And if you’re wondering…yes, Hixson tuned in to portions of Ken Burns’ new PBS documentary “The Vietnam War”.

“Yeah I saw some it, but I didn’t need to watch it to know what happened. It was terrible…I was in it. It was a way for politicians to get something going so they could get reelected. In the end, it didn’t really do anything. Everything went back to the way it was and then we paid to fix it all back up.”

Vietnam Veterans Memorial

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial, located just north of the Lincoln Memorial, is a national memorial in Washington, D.C., and is open 24 hours a day. It honors U.S. service members of the U.S. armed forces who fought in the Vietnam War, service members who died in service in Vietnam/South East Asia, and those service members who were unaccounted for (Missing In Action) during the War.

The main part of the memorial was completed in 1982. The memorial is maintained by the U.S. National Park Service, and receives around 3 million visitors each year. The Memorial Wall was designed by American architect Maya Lin. There are 58,195 names typeset onto the wall of service men and women who gave their lives in service of the Vietnam War,

@DonRadebaugh

Or find me on my Facebook Fan Page at History Mystery Man.

Wayne is highly respected in the ARCA garage, I always take time to talk to him. He is a good man, a good friend, and a great American. SEMPER FI

Never realized Wayne went thru Vietnam. His bio is very interesting and I thank him for what he and his buddies did back then. I served in the Air Force from 67-71 and was a lucky one to not go to Vietnam. Wayne is an excellent Arca owner example. If you need help, just ask him and he’s there with you. Thank you Wayne.

Thanks for taking the time to check it out Rush…

always thought a lot of wayne .Great story Don .Keep it up Itsd good to hear about all the race car people. WE never know how they got here

to race cars

Thanks Jack…