JOHNSON’S ISLAND, Ohio — If you’re in the right age bracket, you would remember Gilligan’s Island. But regardless of how many years you have, I’d be willing to wager you’re not all too familiar with Johnson’s Island. To cut to the chase, one is fiction; unfortunately, the other is not.

Folks from around the world have certainly seen Johnson’s Island without ever realizing it. Put it this way…if you’ve ever been atop one of the roller coasters at Sandusky, Ohio’s Cedar Point, then you’ve seen Johnson’s Island. It’s an easy glance just a few miles across the Sandusky Bay. You can’t help but notice all the new development on the historic island…brand new homes going up left and right. Some folks, without possibly knowing, have built on sacred and hallowed ground…the possible repercussions, if any, not yet visible.

It’s hard to imagine or get a grip on what happened on the island. Given its close proximity to one of the world’s most famous amusement parks, the two are joined at the hip yet will forever remain an unlikely pair.

Cedar Point is all about the fun. On the other hand, there probably wasn’t a great deal of amusement on Johnson’s Island, not if you were one of 12,000 Confederate prisoners of war during America’s Civil War.

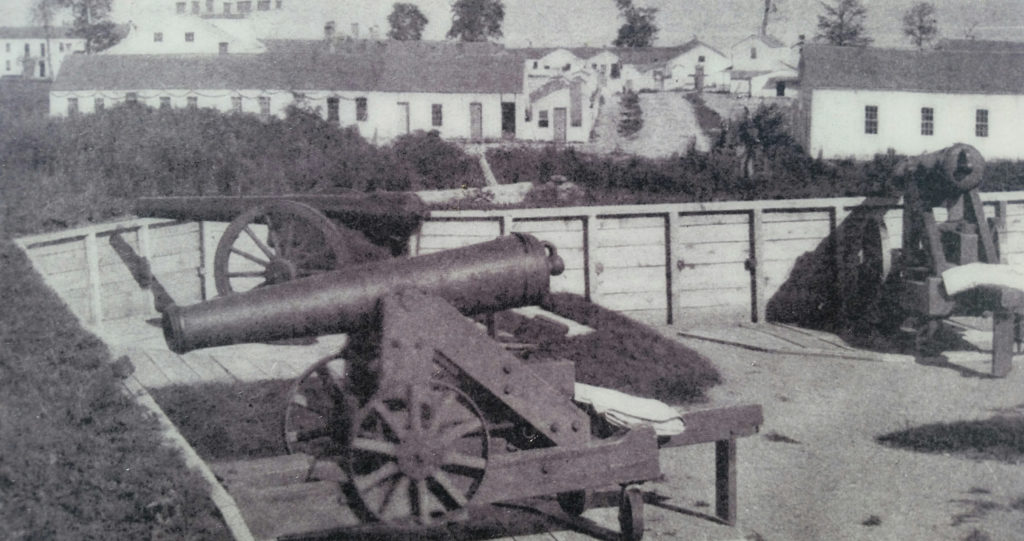

On November 15, 1861, the War Department sectioned off half the island and began constructing a 15-acre prison camp along the southeast shore. When it was done, a 14-foot-tall wooden stockade circled 13 barracks, one of which served as a hospital. There were also 40 structures outside the complex that housed prison staff. Artillery looked down on the barracks to guard against potential insurrection.

In June 1862, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered all Confederate officers held at Camp Chase prison in Columbus, Ohio to be moved to Johnson’s Island. It became the official prison for Confederate officers. Non-officers were imprisoned there too.

Over the course of the war, as many as 12,000 prisoners were confined to Johnson’s Island, and 239 died there, a remarkably low number compared to other Civil War prisons, despite the harsh climate and remote conditions. Confederate soldier David T. J. Wood was the first recorded death at the prison camp in May of 1862. William Michael, who died in June of 1865, was the last to die at Johnson’s Island, the month the prison closed and more than a month after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, officially ending the Civil War.

Each day began and ended with formation and roll call. While the prisoners were free to move about inside the barracks, boredom was as much an enemy as the opposing side. To keep occupied, prisoners organized their own baseball games which were played inside the open areas. The YMCA also donated some 600 books, mostly classical and religious works as books on politics and war were forbidden. Lively debates between the prisoners were as common as poker games.

From the opening of the prison to 1864 prisoners were well fed, just as well as Union soldiers in the field. But as reports surfaced about the starving Union prisoners of war in the south — mostly as a result of dwindling southern supplies — Stanton ordered half rations for the island prisoners. To make up for it, rat hunts were conducted by prisoners to combat hunger.

When prisoners died, they were buried on the spot, just about a half-mile from camp. The soft, sandy soil made digging graves easier work, yet they couldn’t go much deeper than 4-5 feet with solid bedrock just under the sand. Each grave was marked by a wooden headboard. In 1890, as result of a group of Georgia journalists, marble headstones were erected, many of which remain today.

When prisoners died, they were buried on the spot, just about a half-mile from camp. The soft, sandy soil made digging graves easier work, yet they couldn’t go much deeper than 4-5 feet with solid bedrock just under the sand. Each grave was marked by a wooden headboard. In 1890, as result of a group of Georgia journalists, marble headstones were erected, many of which remain today.

In 1910, Mary Patton Hudson, the chapter leader of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), raised the money to erect a large monument, a bronze statue of a Confederate soldier near the bayside entrance of the cemetery. In 1931, 11 years after Hudson’s death, the UDC donated the cemetery to the U.S. government.

There’s nothing left of the old prison now, nothing except gravestones marking the men who died there, many of which are marked with an “unknown” status. That, and the modern-day homes that now encircle the sacred ground, the cemetery enclosed by an old rod iron fence. Write or wrong, good or bad, Johnson’s Island is now a resort area less than three miles from an amusement park. I can only wonder if the souls of the prisoners who suffered and died there are okay with that. Apparently, the people in the mostly fancy homes that surround the cemetery are.

@DonRadebaugh

Don, you have yet to write a boring story. These articles are why I don’t understand reading fiction, there are so many stories that are real, why go for fiction? Not to mention your writing is exemplary.

Loved the story!

Thanks. You should read the one on Johnstown Flood…