By Don Radebaugh — Abraham Lincoln was largely self-taught, which makes his rise to the presidency of the United States that more incredible. Based on what we know, he had, all totaled, about a year or less of formal education, and that was all in “blab” schools during his boyhood years . They were blab schools because children would recite their lessons out loud. Writing utensils, paper, books and other essentials were scarce on the frontier so lessons were often heard, rather than seen. Possibly, that’s why Lincoln, in his adult years, read aloud, which tended to annoy the people around him. He always said that information was easier to retain if he could engage two senses (seeing and hearing) while he read, rather than just the sense of sight.

“There are some schools, so called; but no qualification was ever required of a teacher beyond ‘readin, writin, and cipherin’ to the Rule of Three. If a straggler supposed to understand Latin happened to sojourn in the neighborhood, he was looked upon as a wizzard (sic). There was nothing to excite ambition for education. Of course when I came of age I did not know much. Still somehow, I could read, write and cipher to the Rule of Three; but that was all. I have not been to school since. The little advance I now have upon this store of education, I have picked up from time to time under the pressure of necessity.”

So where and when did Lincoln teach himself all the essentials that would shape the man he would become?

So where and when did Lincoln teach himself all the essentials that would shape the man he would become?

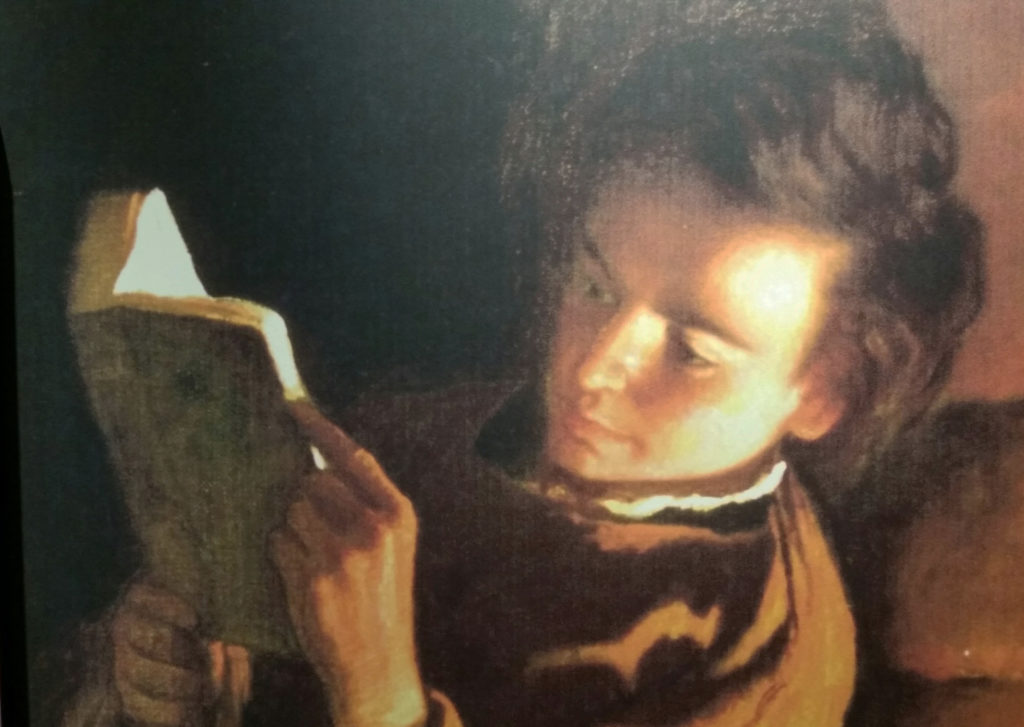

If his boyhood growing up and Kentucky and southern Indiana could be considered his “grade school” years, then his time in New Salem, Illinois served as his “University.” As a boy in Indiana, Lincoln literally read everything he could get his hands on — the Bible, Aesop’s Fables, Pilgrim’s Progress, Robinson Crusoe and the Life of Washington.

According to his stepmother Sarah Bush Johnston, “Abe read all the books he could lay his hands on, and when he came across a passage that struck him he would write it down. He would then repeat it over to himself again and again. When it was fixed in his mind to suit him, he never lost that fact or his understanding of it.”

And when he ran out of books, he read the same ones over and over. He read so much that many thought Lincoln was lazy…little did they understand that he was programming his mind for greater things beyond the back-breaking, mundane work on the farm.

New Salem, about 20 miles northwest of Springfield, Illinois, is an interesting and fascinating place. Thankfully, in large part because of William Randolph Hearst, Lincoln’s New Salem State Historic Site is preserved for future generations to explore and enjoy. For me, it’s an annual trek that always amazes and never disappoints…and it never gets old. The nearby town of Petersburg, historically charming, is just a bonus.

New Salem was founded on a bluff above the Sangamon River in 1829, and was all but a ghost town just 11 years later. It almost seemed to rise and fall with Lincoln who arrived in the spring of 1831 as a “strange, friendless, uneducated, penniless boy, working on a flatboat,” and left in April of 1837 as a military veteran, postmaster, deputy surveyor, politician and lawyer. Granted, New Salem’s fate may have been sealed when the post office moved from New Salem to Petersburg on May 30, 1836. And when the Illinois Legislature, of which Lincoln was a part of, created Menard County and made Petersburg the county seat in February of 1839, New Salem’s days were officially numbered. Yet, despite the municipal technicalities, the life energy of the once promising frontier town seemed to fizzle out after Lincoln left.

Twenty-two year old Abraham Lincoln, who had just set out on his own, landed in New Salem by accident in the spring of 1831. He was already in nearby Sangamo Town, building a flatboat for Denton Offutt who hired Lincoln and his cousin John Hanks and stepbrother John D. Johnston to take a flatboat of goods to New Orleans. On their way up the Sangamon River, their flatboat got hung up on a mill dam at New Salem. A crowd gathered on the riverbank where Lincoln took charge. #Leadership.

He was dressed in “a pair of blue jeans trowsers indefinitely rolled up, a cotton shirt, striped white and blue…and a buckeye-chip hat for which a demand of 12 and a half cents would have been exorbitant.”

With the bow up in the air and the stern going under, Lincoln devised a plan. He went ashore, scaled the bluff and borrowed an auger from Henry Onstot’s cooper shop in the new village of “Salem.” Then, after shifting a good bit of the cargo forward, he drilled a hole in the bow, allowing the water to drain from the stern forward. With the water drained and the stern back afloat, Lincoln plugged the hole and eased the boat over the dam. So impressed was Offutt with Lincoln that he set forth in motion a plan to open a general store at New Salem and hire Lincoln as the store clerk upon his return from New Orleans.

Lincoln got back to New Salem in late July, 1831, voted for the first time on August 1 and went to work in Offutt’s store sometime in September. William G. Greene was hired to be Lincoln’s assistant. Both men made the store their home. At 6 ft. 4 in. Lincoln quickly became the center of attention; his physical strength stood out from the rest. It wasn’t long before the tall, lanky newcomer was challenged to a wrestling match by local roughen Jack Armstrong. The famous wrestling match was born from a $10 bet between Offutt, who bragged about Lincoln’s physical strength, and Bill Clary, who had a next door grocery store. When Armstrong began to get the worst of it, his friends stepped in to help. Lincoln offered to fight any of them singly. None accepted. With his honor restored, Lincoln went about is business. He and Armstrong became lifelong friends.

Sometime in the winter of 1831-32, Lincoln joined the local debating society and startled the locals with, not just his physical prowess, but his mental capacity. Sometime in 1832, Lincoln reached out to the local school teacher Mentor Graham. Graham suggested that Lincoln get a copy of Kirkham’s Grammar, and Graham helped his newest student with some of the difficult parts. It didn’t stop there. Next Lincoln took on mathematics and mastered Euclidean geometry. He also studied history and literature with encouragement from his New Salem friend Jack Kelso.

On March 29, 1832, Lincoln announced his candidacy for the Illinois Legislature in writing, which was printed in the Sangamo Journal.

“Every man is said to have his peculiar ambition. Whether it is true or not, I can say for one that I have no other so great as that of being truly esteemed of my fellow men, by rendering myself worthy of their esteem. How far I shall succeed in gratifying this ambition is yet to be developed. I am young and unknown to many of you. I was born and have ever remained in the most humble walks of life. I have no wealthy or popular relations to recommend me. My case is thrown exclusively upon the independent voters of this county, and if elected they will have conferred a favor upon me, for which I shall be unremitting in my labors to compensate. But if the good people in their wisdom shall see fit to keep me in the background, I have been too familiar with disappointments to be very much chagrined.”

A seat in the Illinois House would have been a welcome sight for the young aspiring New Salem resident considering Offutt’s store would be closing in the spring of ’32 and Lincoln would find himself unemployed. He also ran out of time to effectively campaign for the Legislature when on April 19, 1832 a proclamation from Illinois governor John Reynolds called for volunteers to help repel Chief Black Hawk and his Braves who re-crossed back into Illinois. With Offutt’s store about ready to “wink out” Lincoln had nothing better to do and enlisted his services in the Black Hawk War. Lincoln was elected captain of his company and off they went, marching from place to place. He never actually saw any active fighting although in later years he said that he “had a good many bloody struggles with musquitoes (sic).” On July 10, he was honorably mustered out of service and returned home to New Salem toward the end of July, leaving him just two weeks to campaign for office. It wasn’t enough…Lincoln lost his first election, coming in eighth out of 13 candidates; although he polled very well in his own precinct, getting 277 of 300 votes.

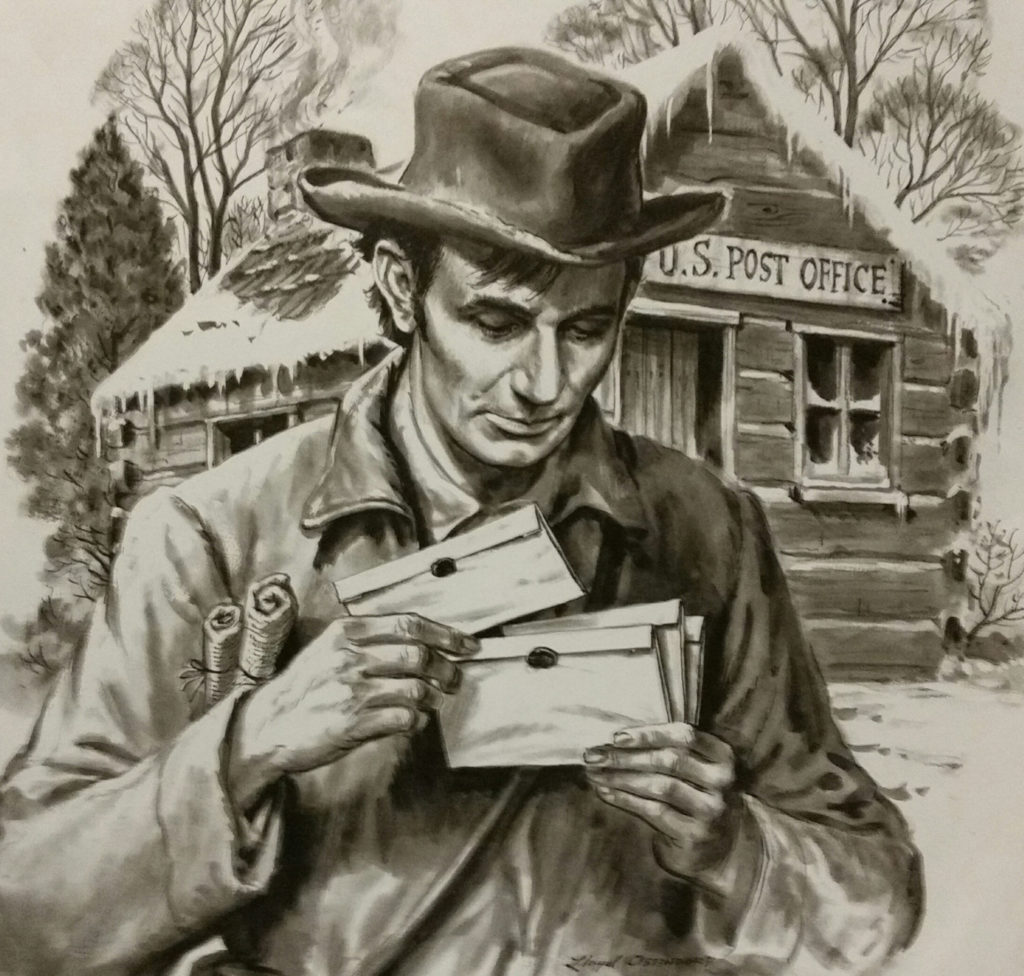

Without steady employment Lincoln did odd jobs for his New Salem neighbors, which included anything from splitting rails to grunt work to even drawing up contracts and deeds. By late August Lincoln decided to take another run at storekeeping and partnered with William Berry. They eventually bought out another stock of goods and moved into another store across the street. Then on May 7, 1833 Lincoln was also appointed New Salem’s postmaster. He relished in the role and the responsibility. It also allowed him to read all the different newspapers that circulated through the post office, adding to his frontier education. Unfortunately, it paid very little and Lincoln, who borrowed the money to become a storekeeper, went deeper and deeper in debt. To bring in more money, Lincoln took up surveying and became deputy surveyor to John Calhoun sometime in 1833. Lincoln studied geometry, trigonometry and read books on surveying. Then he purchased the basic equipment and a horse on credit and “went at it.”

Without steady employment Lincoln did odd jobs for his New Salem neighbors, which included anything from splitting rails to grunt work to even drawing up contracts and deeds. By late August Lincoln decided to take another run at storekeeping and partnered with William Berry. They eventually bought out another stock of goods and moved into another store across the street. Then on May 7, 1833 Lincoln was also appointed New Salem’s postmaster. He relished in the role and the responsibility. It also allowed him to read all the different newspapers that circulated through the post office, adding to his frontier education. Unfortunately, it paid very little and Lincoln, who borrowed the money to become a storekeeper, went deeper and deeper in debt. To bring in more money, Lincoln took up surveying and became deputy surveyor to John Calhoun sometime in 1833. Lincoln studied geometry, trigonometry and read books on surveying. Then he purchased the basic equipment and a horse on credit and “went at it.”

Lincoln knew he had to do something to earn his keep. His partnership with Berry was going nowhere and by the end of 1833, the store failed leaving both deep in debt. Despite his mounting debt Lincoln pressed on with odd jobs throughout 1834 and took another run at the Illinois Legislature. By now, he was well known in and around Sangamon County. If they didn’t agree with his politics, it mattered little to the people who came to know and admire his honesty, integrity and character. When judgments were brought against him for his debt, his surveying equipment and horse were confiscated by the courts. When his equipment came up for auction, his friend “Uncle Jimmy Short” purchased Lincoln’s surveying tools and promptly returned them so Lincoln could go on earning a living. When the final votes were counted on August 4, 1834, Lincoln was elected to the Illinois Ninth General Assembly where he was to take his seat in Vandalia, Illinois on December 1. In the intervening four months, and on a recommendation from his future law partner John Todd Stuart, Lincoln took up the study of law, borrowing local law books. Before leaving New Salem for the state capital in Vandalia, a local farmer, Coleman Smoot, loaned Lincoln $200 for a new suit of clothes. It seemed as though everyone who knew him was ready and willing to help. Beyond their acts of kindness, Lincoln’s neighbors saw something in him and were willing to invest their time, energy and resources to help his visions come to life. They not only befriended him, they fed him, helped clothe him and gave him a warm place to lay down at night.

While in New Salem he boarded with the local cooper Henry Onstot and his family, Nancy and Bowling Green, Jack and Hannah Armstrong, the Rutledge family and others. James Rutledge, who co-founded New Salem with John Camron, ran a local tavern. Lincoln got to know Rutledge’s daughter Ann Rutledge when he boarded there in 1832. Many believe that Lincoln and Ann fell in love, and when she died of Typhoid on August 25, 1835, according to his New Salem neighbors, Lincoln was visibly distraught and went into a deep depression. As to the extent of their relationship, we can never know for sure…it’s just another piece of the New Salem puzzle and “Lincoln Lore” that continues to fascinate.

When the post office moved from New Salem to Petersburg in March of ’36, Lincoln would no longer serve as postmaster; but he kept up his surveying duties in earnest, laying out town plats for Petersburg, Bath, Athens, Huron, Albany and New Boston. He was also elected to his second term in the Illinois House, his second of four consecutive terms he would serve over his early political career. And on March 1, 1837, as a result of his own studies, was admitted to the bar for the state of Illinois. Lincoln demonstrated early on as to the direction of his politics. On March 3 he entered and signed, as “Representative from the county of Sangamon” his first formal protest against the institution of slavery.

“that the institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy…”

With the new state capital headed for Springfield, legislation promoted by Lincoln, and with nearby Petersburg gaining strength, it was time for Lincoln to move on; but not before New Salem served him so well, not only for the frontier lessons it taught, but for the friends he earned and would keep his entire life. Realizing he needed a change to establish himself as a lawyer and to advance his political career, Lincoln left New Salem for good and moved to Springfield on April 15, 1837. Less than four years later, New Salem would be no more.

By 1860, nothing much remained of “Old Salem.” But after Lincoln’s death in 1865, interest began to grow regarding the town and space in time that helped graduate Lincoln to the highest office in America. By 1875 tourists began climbing the hill to see the former location of Offutt’s store where it all began. Parthena Hill, the widow of New Salem merchant and entrepreneur Sam Hill, was still living in 1880 and produced a map of New Salem showing the location of the buildings. In 1884, William Greene, who roomed with Lincoln at New Salem, accompanied a reporter for the Chicago Tribune and pointed out where the stores once stood. Other surviving New Salem residents added their two cents. Interest in the site continued to grow and really gained strength when on August 17, 1906 William Randolph Hearst bought the land for $11,000 and deeded it in trust to the local Old Salem Chautauqua Association. In 1918, based on the available maps and archeological digs, construction began on the site to restore it. On February 1, 1919, the state of Illinois granted state park status to “Old Salem.”

Most of the log homes are constructed, as best as we understand, on their original foundations, give or take. When the cooper Henry Onstot left New Salem in 1840 and moved to Petersburg, as so many residents did, he removed his shop and home to Petersburg where he re-erected both. His cooper shop remained in Petersburg until 1922 when it was taken back to its original foundation at New Salem. The cooper shop remains the only original structure in New Salem. Onstot’s original home remains in Petersburg; but with a house now built around it. I was invited inside once by the current owner who showed me an original log wall, visible through an intended hole in the drywall that surrounds the original wooden structure. Fascinating.

In 1985, the name of the Park was officially changed to Lincoln’s New Salem State Historic Site. Today the site includes an exceptionally nice visitor’s center and museum as well as the 500-seat Kelso Hollow Theater where several productions (Theatre in the Park) are offered throughout the year. So cool.

Like so many Lincoln sites, for me, New Salem is a place I go to pause, reflect and wonder about what happened there so many years ago when a tall, lanky newcomer stumbled upon the place that would change him forever, and ultimately, the country he would one day lead. On this particular day in late summer, it just so happened that direct descendents of the Onstots were visiting New Salem. It was a rare treat for me to meet them and make that connection. Thankfully, they were as interested in their heritage as I was, and the conversation we shared was one I won’t forget. They graciously allowed me to take their picture inside the original cooper shop.

There’s just something about New Salem that grabs me and pulls me in. When I’m there, I get so switched on and tuned in. What I wouldn’t give to spend just one day there during Lincoln’s time…to see and feel the frontier village in all its glory and authenticity. Maybe that’s why I find myself there year after year, camping out at the state park, enjoying the theatre productions and visiting the village where Lincoln walked and talked. It’s one of my favorite places, and when it’s time to make my annual pilgrimage next year, it’ll be like seeing the place for the first time, just like it was in 1834ish when young Abraham Lincoln would kick back against a tree, a copy of Kirkham’s Grammar wedged between his long boney fingers…deep in thought.

Follow me on Twitter @DonRadebaugh or check out/like my Facebook page.

Sources:

New Salem, a History of Lincoln’s Alma Mater, by Joseph M. Di Cola, Copyright 2017

Lincoln’s New Salem, by Benjamin P. Thomas, Copyright 1954

Very good stuff, Mr. Lincoln. Well researched , fascinating as usual!

My favorite place in central Illinois. There’s something powerful being in New Salem when it’s quiet and you can smell the smoke from the fireplaces; it’s easy to imagine it’s the 1830’s on a day like that.

Great article. A lot for knowing father abe.