By Don Radebaugh – In 1915, the world-renowned “Spoon River Anthology” was published and its author revealed. Edgar Lee Masters’ life, good and bad, would never be the same, nor would the small town folks he exposed inside the Anthology. Despite the wide fame and narrow fortune the Spoon River Anthology brought the Illinois Prairie Poet, the firestorm the book created would haunt him for his remaining years.

Although he could never duplicate its success, Spoon River Anthology dominated the American literary scene for several years following its publication, bringing Masters wide-spread fame.

Spoon River was a fictitious town in Illinois. In real life, it was a combination of Petersburg and Lewistown, Illinois, where Masters grew up…in Petersburg through his 11th year, and in Lewistown until he was 24. As one might imagine, residents of Lewistown, void of special childhood memories he kept of Petersburg, carried the brunt of his less than charming blows that made him famous. As an interesting dichotomy, it’s worth noting that Petersburg was more southern in its ancestry while Lewistown leaned more northern, despite the close proximity of the two prairie towns.

The poems were written in free-verse style, in the ‘first-person’, and for many, from the grave, which cast an eerie glow over the whole thing right from the start. He exposed and spoke for the town drunkard, the whore, the killer, the infidel, the crook, the hero, the villain, the wealthy, the poor, the philanthropist, the evil-doer, the swindler, the unhappy married housewife and more…no one was spared. He literally took on the identities of the deceased and exposed their secrets. If he embellished along the way, so be it. After all, this is literature, mind you.

Several of the poems were first published in a series in “Reedy’s Mirror” out of St. Louis in 1914, under the pseudo name Webster Ford. The publisher, William Reedy, who would remain a lifelong friend, convinced Masters to come up with a title and package the Anthology in a book, and reveal himself as the author. Masters eventually agreed and came up with Spoon River Anthology. The real Spoon River meanders along just outside of Lewistown.

When the book first went to market, it was literally flying off the shelves. With a Greek Anthology feel, the dead were echoing from the graves…talking about their small town troubled lives in Spoon River, AKA Petersburg and Lewistown. If America had a magically-euphoric, charming, homespun view of small town America, Spoon River exposed a darker side. And when the people in and around the Sangamon and Spoon River valley first came across the words in the Anthology, many were horrified at what they read. Masters was clearly talking about their family members, but with fictitious names. And in some cases, the epitaphs found in the Anthology were about people who were still alive in 1915. If they weren’t reading about their deceased family members, they were reading about themselves.

When the book first went to market, it was literally flying off the shelves. With a Greek Anthology feel, the dead were echoing from the graves…talking about their small town troubled lives in Spoon River, AKA Petersburg and Lewistown. If America had a magically-euphoric, charming, homespun view of small town America, Spoon River exposed a darker side. And when the people in and around the Sangamon and Spoon River valley first came across the words in the Anthology, many were horrified at what they read. Masters was clearly talking about their family members, but with fictitious names. And in some cases, the epitaphs found in the Anthology were about people who were still alive in 1915. If they weren’t reading about their deceased family members, they were reading about themselves.

The book caused such a stir, it would not be until the mid-1970s before Spoon River Anthology would be for sale in Lewistown. Many of the small town residents in the Anthology are buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in Lewistown. Masters, in the book, shortened it up to “The Hill.”

In a twist of irony, Masters himself had his share of questionable personality traits that somehow escaped publication initially, but would be eventually exposed over the years nonetheless. Arguably a brilliant writer and an effective lawyer, Masters was a womanizer who could not, would not stay faithful to his wives. He was highly critical of his peers, arguably inept with his own business affairs and squandered whatever wealth he earned. He was often his own worst enemy.

Yet, when the Anthology first broke, he got what he so sought…worldwide fame as a writer. He was the Mark Twain of his time. But, unlike Twain, who wrote one well-traveled book after another, Masters could never reproduce the success of Spoon River. From the Anthology on, nothing ever measured up. It wasn’t as though he didn’t try either. Over his long career, while balancing his busy law practice, he wrote constantly…plays, novels, essays and biographies; but nothing ever took hold the way Spoon River did. He even tried to cash in on Abraham Lincoln, finishing up a biography “Lincoln: the Man” in 1931. And who better to write about Lincoln, Masters believed. After all, he grew up in Petersburg, a town frequented by Lincoln. Masters knew people who knew Lincoln. His father, Hardin Masters, was a law partner of William Herndon. Herndon was Lincoln’s last law partner. But when the book came on the market, readers found a scathing biography on the 16th President. Masters, who lined up politically opposite of Lincoln, fervently opposed the “Great Emancipator” and reflected Lincoln in a negative light. The world, in the early 1930s, just wasn’t ready for that, and it further damaged his reputation and career. The book flopped.

My Edgar Lee Masters adventure started in Petersburg, one of my all-time favorite small towns. I had known about Masters for years…couldn’t help but notice his gravestone at Oakland Cemetery in Petersburg…but I never really dug in until last summer. When I heard about “The Hill” my “fascinationometer” went through the roof. His story continues to fascinate me.

He was born in Garnett, Kansas on August 23, 1868; but soon after his birth, he moved with his parents, Hardin and Emma Masters, to Petersburg where he lived in several different residences, including the beautifully-restored cottage that still exists on the northwest corner of Eighth and Jackson Streets.  The home is available for tours and the ladies that manage the property are extremely helpful and knowledgeable. It was inside the cottage where the ladies tipped me off about a biography on Edgar Lee Masters that I couldn’t wait to get my hands on. They also suggested I spend some time in Lewistown where I could learn more and visit “The Hill.” By now, I was hooked, and couldn’t wait to get there.

The home is available for tours and the ladies that manage the property are extremely helpful and knowledgeable. It was inside the cottage where the ladies tipped me off about a biography on Edgar Lee Masters that I couldn’t wait to get my hands on. They also suggested I spend some time in Lewistown where I could learn more and visit “The Hill.” By now, I was hooked, and couldn’t wait to get there.

In the book, “Edgar Lee Masters, A Biography,” I learned that Masters never received the affection he desperately longed for from his parents, but he did his best to make up for it when he visited his paternal grandparents’ farm just north of Petersburg. While he dearly loved both, it was his grandmother Lucinda Masters he adored most, and she, him. And it was in Petersburg where Masters’ more pleasant view of small town America grew roots. However, things changed for Masters in a big way when, in the summer of 1880, the family uprooted for Lewistown, about 40 miles northwest of Petersburg.

Masters moved from boyhood to manhood in Lewistown where he began to form his own strong opinions about the world around him. He developed his own views on the social, economic and political issues he saw in front of him, and grew angrier with injustice. He had access to his father’s law office files that offered up inside information on the local towns people. In addition to being a lawyer, his father also served as Lewistown’s Mayor, exposing Masters to local politics, shedding more light on the people who would eventually become characters in the Anthology. Masters also spent a good deal of time at the local blacksmith shop just across the street from his house. The blacksmith shop was a favorite gathering place for many as the center of local gossip. In short, Masters’ Lewistown upbringing provided insight into his neighbors that most had no access to. And before leaving for Chicago in 1892 to try his own experiment as a lawyer, he carried with him everything he learned in Lewistown…all tucked away inside his exceptional memory.

In the hustle and bustle of Chicago, Masters drudged through his law career to earn a living while yearning to be recognized as an acclaimed author. It was time to get serious and start writing in earnest.

It was also time to “tie the knot” after Masters met Helen Jenkins, the pretty daughter of a railroad executive. Masters, whose law career struggled early on, also saw an opportunity to advance his financial status. And on June 21, 1898, he married Helen. The marriage seemed doomed from the start. “Like a man going to the electric chair,” Masters later wrote. It wasn’t long before Masters stepped outside the marriage to satisfy his unhappiness. “Not finding all in my home that I wanted for the stuff of living, I…always kept my own way.” It was a series a love affairs, one after the other, that Masters could not refrain from…including one that lasted nearly two years after he fell in love with an artist by the name of Tennessee Mitchell. But Mitchell was just one in long line of extra-marital affairs for Masters.

And when worldwide fame came his way after Spoon River, he grew more irritated over the fact that the Spoon River success did not necessarily equate to financial success…not enough to afford to walk away from his law career he so despised. And there was his free-spirited lifestyle he had to keep up with. Moreover, his sudden notoriety chewed up way too much time while he wondered what to do with his law career and how to keep up with his living expenses. And while Masters banished in the glow of the affirmation from his contemporaries, he did not handle his critics well. There were also two daughters to support now; but his writing opportunities and law practice provided little time for the two little girls. Two more sons would follow, his fourth child through another marriage.

Despite his busy, convoluted schedule, Masters still found time to write, and write he did. He wrote biographies, plays, sketches, poetry, novels and more. Between novels and biographies alone, he wrote more than 50 books over his long literary career. While some showed signs of life in print, none took off and soared like the Anthology. The advances he received from publishers were often more than the proceeds from sales.

And, with Tennessee Mitchell gone from this life, he pursued a new love interest in which he had a long love affair. Her name was Lillian Pampell Wilson, “the magic princess of the sleeping palace.” Lillian was a wealthy widow who owned a mansion in Marion, Indiana, a hand-me-down home from her deceased husband. It became a frequent stop for Masters, all the while trying to remove himself from his first marriage, the endless expense of which, continued to mount.

But like all of Masters’ relationships, Lillian didn’t work out either. As she began to lose interest in the “great poet,” Masters, fed up with his love life, his waning literary career, a law practice that was nearly no more, mounting debt and an abundance of critics, decided it was time to make another move. With his wife Helen finally granting him a divorce in 1922, Masters, in his 55th year, with what little he now owned, packed his bags and moved to New York in 1923.

If Masters had little money, he still had his fame and was entertained constantly by his literary peers and ladies alike. Even President Teddy Roosevelt arranged to meet the great Prairie Poet from small town Illinois. It wasn’t long before Masters was courting a young actress by the name of Ellen Coyne, who, at 24, was not half his age. He had dated her briefly before he left Chicago. She would become his second wife and the mother of his fourth son, Hilary. They would remain married to the end.

If Masters had little money, he still had his fame and was entertained constantly by his literary peers and ladies alike. Even President Teddy Roosevelt arranged to meet the great Prairie Poet from small town Illinois. It wasn’t long before Masters was courting a young actress by the name of Ellen Coyne, who, at 24, was not half his age. He had dated her briefly before he left Chicago. She would become his second wife and the mother of his fourth son, Hilary. They would remain married to the end.

Unfortunately, the magic of the “Big Apple” did not find its way into Masters’ literary career, although he continued to write nonetheless. He would also find his way to more affairs when Ellen was away. But nothing or no one ever seemed to satisfy the aging poet. His health declined with the years, and eventually Ellen had Masters admitted into a nursing home in Melrose Park, Pennsylvania, just outside Philadelphia where he suffered from a variety of ailments, including pneumonia, which he had endured at least three times before, and once in 1943 that he never fully recovered from.

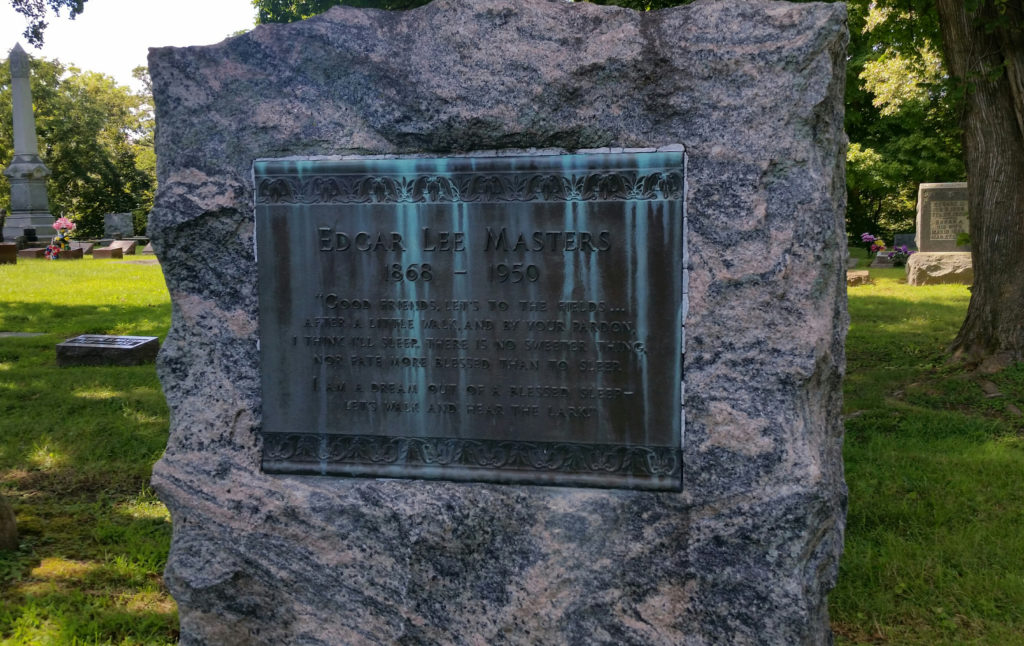

Masters was 81 when he took his final breath on the night of March 5, 1950, leaving behind nothing more than his papers and his copyright to Spoon River Anthology. He died a long way from his boyhood home, but finally found his way back to his “spiritual home” and was buried alongside his beloved grandmother Lucinda Masters at Oakland Cemetery in Petersburg. “I want to be taken back there when I die and be buried by the side of my old grandmother,” he told a friend in 1925, and so he was. Instead of a funeral sermon, Masters arranged for mourners to hear records of his favorite musical selections – Beethoven, Chopin, Dvorak, Sibelius and others. Businesses in Petersburg were respectfully closed on the day of Masters’ funeral.

While Masters no doubt took some literary liberties, he also exposed some truths about small town America that took years to digest…too painful as it was for so many. Ironically, his papers are now safely tucked away inside the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield alongside the President’s archives…the President he despised. In the end, he became a victim of his one and only literary success, one he had no answer for. Spoon River Anthology brought the fame he desired, but it also brought baggage, sadness and despondency. Fortunately, there is renewed interest in Masters’ work, and literary types are taking another look at the Prairie Poet from Petersburg. Could it be that there’s a lot more to Masters genius than Spoon River? I like to think there is.

I spent a few more hours walking the grounds at Oak Hill Cemetery…up on “The Hill.” It’s a bit of a tourist attraction now. The graves are all marked, and a brochure will lead you to all the characters in Masters’ Anthology…their fictitious names on one side, their real names on the other. But on this day, I was the only tourist on “The Hill”, and with the sun getting lower in the sky, my nerves were beginning to wane and so I came down from that hill and moved on.

Besides, I had one more stop to make before I left Lewistown. I just had to see the real Spoon River, so I steered for nearby Bernadotte, Illinois. Masters often spoke of Bernadotte where the Spoon River meandered over an old mill dam. I went to that exact location. The mill is gone but Spoon River still meanders with a good bit of might before finding its way to the Illinois River at Havana. I could have sat there all day, alone with my thoughts, watching the mystic Spoon River spill over the dam and move away with the dead souls from the Anthology. William Reedy, the publisher of Spoon River Anthology, said it best, “Spoon River is like that mythical river in some old anthology that flows all around the whole world.” Lewistown could be any small town.

My journey ultimately ended where it began, back in Petersburg the next morning where I made my way to Oakland Cemetery. I couldn’t help but notice that Masters’ epitaph on his gravestone read much differently than those unfortunate souls described in the Spoon River Anthology. From Masters’ own pen, his gravestone reads….

My journey ultimately ended where it began, back in Petersburg the next morning where I made my way to Oakland Cemetery. I couldn’t help but notice that Masters’ epitaph on his gravestone read much differently than those unfortunate souls described in the Spoon River Anthology. From Masters’ own pen, his gravestone reads….

Good friends, let’s to the fields…

After a little walk, and by your pardon,

I think I’ll sleep. There is no sweeter thing,

Nor fate more blessed than to sleep.

I am a dream out of a blessed sleep.

Let’s walk and hear the lark.

For me, my favorite poem from Masters didn’t come from his most renowned works in Spoon River, but rather from his short pamphlet “Illinois Poems”. Here are just a few of the graphs from “Petersburg”

Petersburg is my heart’s home.

There I knew at first earth’s sun and air;

Still I can see the hills around it,

The people that walked its business square.Nestled near where the river creeps,

Petersburg, like an old man sleeps;

The pioneers are gone, but others

Walk the business square where memory keeps.And why they came and why they went,

Why we were into their places sent

Brings wonder that daily overcomes us

For what we mean and what they meant.

Notes: Each fall, there is a really cool Spoon River Valley Scenic drive festival of events through Fulton County, Illinois. The Spoon River and Sangamon River valleys are beautiful anytime of year, and especially so in October, which is when the Spoon River festival takes place annually. For more, visit http://www.spoonriverdrive.org/

@DonRadebaugh

Sources:

Edgar Lee Masters, A Biography, by Herbert K. Russell, Copyright 2001

Spoon River Anthology, by Edgar Lee Masters, Copyright 1915

Boyhood home of Edgar Lee Masters, Petersburg, Ill.

EDGAR LEE MASTERS is my cousin..

Interesting…how many generations back? How are you connected? Thanks…HMM

Your unique ability of bringing history to life provides a reader wanting even more. Interesting and informative. Sheri Perry

Geez…thanks. One of the most gratifying compliments I’ve ever received. #Grateful